Today we are delighted to announce the launch of Progress Ireland, a think tank whose mission is to connect Ireland to ideas that will help unlock its potential.

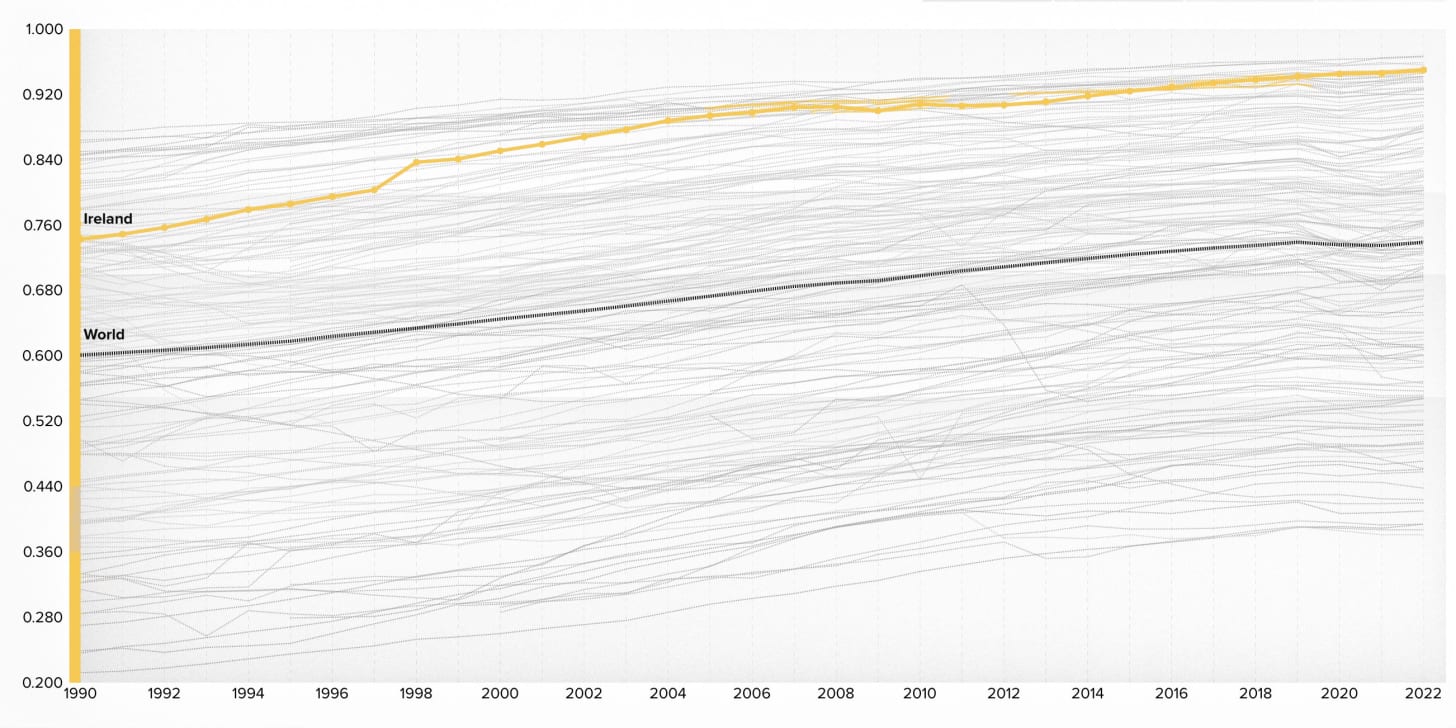

Ireland has come a long way. In 1988, The Economist dubbed Ireland “The poorest of the rich”; today its average net earnings are the third-highest in the EU. In 1990 the UN’s Human Development Index ranked it 25th in the world; today it is ranked 8th.

The success of the Irish economy belies important problems. Ireland doesn’t feel as rich as it is on paper. Despite the third-highest incomes in the EU, Irish consumption is ranked 15th in the EU, behind Romania, Slovenia, Lithuania and Cyprus. The quality of Irish infrastructure is ranked 12th in Europe by company managers.

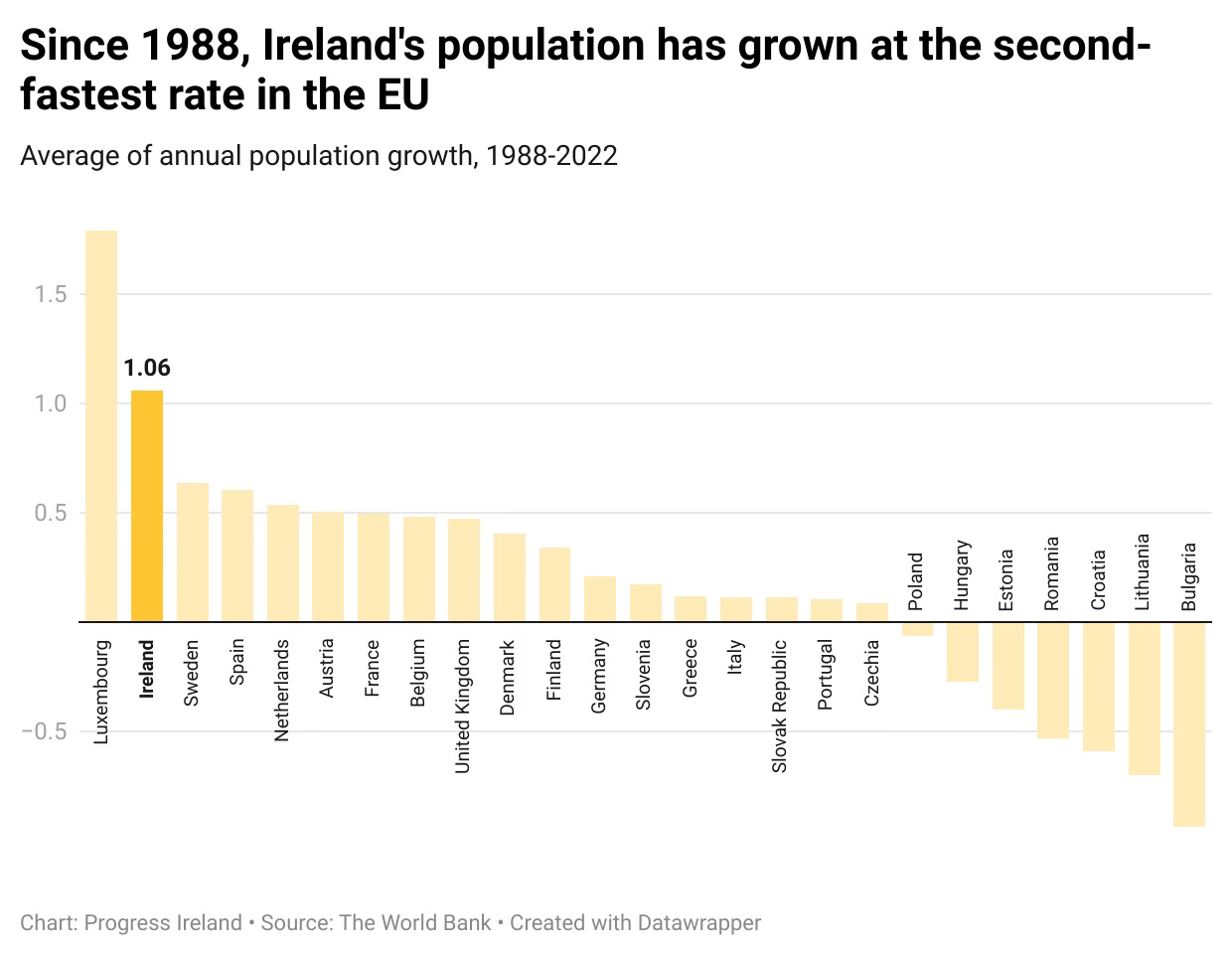

Ireland’s problems are those of growth. Since the Economist’s survey in 1988, Ireland’s population has grown faster than any EU country, bar Luxembourg. That trend is not slowing. Ireland’s population is forecast to grow at the third-fastest rate in the EU through to 2040.1

Ireland is much bigger and richer than it was a generation ago, so it needs much more of… everything. It needs more houses, flats, granny flats, social housing, roads, sewers, trains, floating wind turbines, tunnels, solar panels, hospitals and grid scale batteries.

Ireland is undersupplied with infrastructure. It has another, related problem, which is that it is utterly dependent on foreign multinationals. With a few exceptions, Irish domestic companies punch below their weight. Irish SMEs’ share of gross value added is the smallest of 28 countries studied by the OECD. Irish firms export at less than half the rate of European peer countries.

If a nation must have challenges, these are good ones to have. Ireland has done the hard part. It has built a world-class economy. Now we need to learn how to efficiently convert financial resources into liveable neighbourhoods and successful institutions.

Fundamentally, Ireland needs ambition. We mustn’t stop here. We have the potential to be at the global frontier of living standards, innovation, and culture. We can be the future other countries aspire to.

The steps Ireland skipped

Ireland looks much like any other developed country. But it took a unique path to economic development.

Almost every other developed country bootstrapped their growth. They started with agriculture; built some simple industries; built more complex industries; built big complex cities; built complex transport and other infrastructure; universities and sewerage systems. The process was slow and messy. But it resulted in a complex society with complex cities and complex, world-class companies.

Ireland skipped a few steps. In one generation, Ireland went from a country of agriculture and simple manufacturing to one of world-class companies. Ireland has been able to skip steps by partnering with American companies. Ireland has piggybacked on America’s complexity.

Ireland’s problems are those of growth.

In skipping a few steps of the economic development path, Ireland has been able to quickly grow its income. But it has remained deficient in important ways. It has never had to figure out the hard problems of building complex cities and institutions. Over the last 150 years, while Ireland was a backwater, places like Austria, Japan and Belgium were solving the hard problems of urbanisation and industrialisation by trial and error (though in Japan’s case, there was lots of copying from other countries).

Ireland’s partnership with the USA didn’t happen by accident. We consciously opened up to foreign ideas, technologies, management techniques and capital. The strategy worked perfectly.

Ireland should continue with the same strategy. This time, instead of importing ideas, capital and technology to help Ireland earn money, Ireland needs to import ideas, capital and technology to help Ireland invest money. We need to get better at converting current assets into fixed assets — at turning money into useful things and organisations.

Why a think tank?

Ireland is a small state. There are advantages and disadvantages to being small.

Small governments are closer to their citizens’ problems, and they’re more agile. But small governments don’t have the experience and expertise that comes with scale. They don’t get to learn-by-doing over many projects.

France devolved power from Paris to regional governments after 2003. To set regional governments up for success, the Paris government created a series of think tanks to share knowledge between regional governments. One of these, Cerema, founded in 2014, provides highly technical advice to regional governments on matters of transport, infrastructure, urban planning, and environmental research.

Through Cerema and other think tanks, the French national goverment ensures regional governments are facing outwards, sharing knowledge and learning from each other’s mistakes.

Ireland is deficient in important ways. It has never had to figure out the hard problems of building complex cities and institutions.

Ireland should learn from France. Ireland is not much bigger than the average French region. Like the French regions, it lacks scale. Like them, Ireland could mitigate those problems by facing outwards to other places, raising its ambitions, and consciously importing solutions that have worked.

There is a wide world of policy entrepreneurship and experimentation. Some countries, facing very similar problems to Ireland, solved them with creative and innovative policy. Most countries just trial-and-errored their way to a model that works.

Ireland should not learn by trial and error. It’s too small and its problems are too urgent. It needs an institution whose job it is to systematically study other countries and copy what works.

To be sure, none of Ireland’s problems are simple, and none precisely map onto other places. A tax incentive from Lyon won’t necessarily work in Limerick. There are serious legal, logistical and political obstacles to importing solutions from other places. Progress Ireland’s job will be to understand this context and understand what solutions are suitable in Ireland.

We must be open to solutions, whatever their source. Neither side of the political divide has all the answers: housing is affordable both in “Red Vienna” and in capitalist Chicago.

What we’re working on

Most would accept the proposition that Ireland could benefit from borrowing solutions from overseas. But which ones?

We believe that the question of what Ireland should do is a settled one: the country needs more and better housing, more and better infrastructure, and less reliance on multinationals. The debate in Ireland is over how to achieve these goals. This is where Progress Ireland will operate. We are focused on implementation.

We will choose policies based on three criteria. First: is the problem important? If we solved it, would it matter much? Second: is the problem tractable? Do we have a realistic way to solve it? Third: is the problem neglected? Are we bringing something new to the table?

We are focused on housing, infrastructure, and innovation.

Housing: What rule changes would make it easier to build lots of beautiful homes?

Housing is Ireland’s biggest problem. It has dominated politics for at least five years. In that sense, it isn’t neglected. But Progress Ireland brings a new perspective and a unique set of solutions.

The starting point is that planning systems matter. In the US for example, where there’s significant county-by-county variation in planning rules, there is a strong correlation between the strictness of a city’s planning regime and the affordability of homes.

Ireland should not learn by trial and error. It’s too small and its problems are too urgent. It needs an institution whose job it is to systematically study other countries and copy what works.

It shouldn’t be forgotten that the Irish planning system is unusual. Ireland copied its planning system from the UK, and both places are unusual in the subjectiveness of their planning rules. Planning decisions are adjudicated by planners based on imprecise guidelines. The upshot is that it’s unclear whether planning permission will be granted in advance of an application. This uncertainty is reflected in market prices: the awarding of planning permission to a site can multiply its value many times over.

Uncertainty over planning has hidden costs. The first is it makes small scale development unviable, since only large firms have the financial strength to absorb planning risk. Ireland (and the UK) have much fewer small developers than in jurisdictions with greater planning certainty.

The second cost is that Ireland’s planning system wastes planners’ skills. Planners’ time is spent adjudicating individual applications, rather than the more useful work of master planning.

The third cost is that Ireland’s system is overloaded. There are more applications than staff can cope with. The planning process can take years. Delays add cost to projects, and costs prevent projects from ever going ahead.

Ireland and the UK, with their discretionary planning systems, have the problems you’d expect to see of countries with discretionary planning systems. But many other models exist. Ireland’s planning system is fundamentally different from almost all others in the OECD. Ireland’s outcomes don’t compare well.

The point isn’t that we should rip up Ireland’s planning regime and start again. It’s that incrementally adding more certainty to the planning system will make the country richer and more affordable. Done well, it can be a win-win. It can permit lots of building while attending to neighbours’ concerns. And it has the potential to make a material difference to housing affordability.

Infrastructure: how can we build complex infrastructure as cheaply and efficiently as the best builders in Europe and Asia?

For Ireland to reach its potential, it will have to build more complex infrastructure than it ever has before. The National Children’s Hospital was a foreshadowing of what is to come. In every domain Ireland will need to take on bigger and more complex projects: offshore wind, metro, tunnelled roads, sewerage, transmission and distribution lines.

Building complex infrastructure is about the hardest task a government can undertake. It involves interfacing with dozens of stakeholders and partners. The budgets are enormous and so is the scope for failure.

The question of what Ireland should do is settled: the country needs more housing, more infrastructure, and less reliance on multinationals. The debate is over how to achieve these goals.

There’s a huge difference between the most efficient and least efficient builders of complex infrastructure. For example, efficient countries can deliver a kilometre of metro for 10 per cent the cost of inefficient ones. Worryingly, the inefficient countries look a lot like Ireland. They all speak English.

The places that build efficiently, by contrast, all have something in common: their states have in-house technical expertise. To build complex infrastructure, Ireland needs to build engineering institutions to run the projects.

How can we build a pipeline of innovation from universities through to Irish companies?

Business in Ireland is exceptionally strong, but Irish business is not strong. Foreign multinationals have crowded out domestic companies. The upshot is that Irish living standards and public finances are dependent on US companies and US tax law.

Irish companies are capable of mixing with the best – Flutter, Ryanair, and AerCap each lead their industry. But Ireland has too few of them.

For Ireland to reach its potential, it will have to build more complex infrastructure than it ever has before.

Building world class Irish companies will require technological innovation. Technological innovation requires world class science and research, but at Irish universities, research is not prioritised. Ambition is too low.

There is a chasm between basic research at Irish universities and finished products on the marketplace. Policy structures don’t make it easy to commercialise academic research.

Ireland benefits from technologically sophisticated companies and a skilled workforce. But workers are not rewarded for building their own businesses. Their skills and knowledge stay locked up in the multinationals, with the benefits accruing to US shareholders.

What we believe

We have said we choose subject areas based on what’s important, tractable and neglected. But that begs a further question. What do we define as important?

As much as we would like to imagine ourselves as pragmatic technocrats who are untainted by ideology, when you get down to it, everyone has values. Here are ours:

We believe in ambition. Irish people should aspire to greatness for themselves and their country. Ireland should aspire to the highest standards of living in the world.

We believe in policy. We sincerely believe that evidence-based and creative policymaking can solve Ireland’s biggest problems.

We believe in win-win politics. The policies that are most likely to be implemented, and the ones that work, distribute their benefits widely.

Ireland benefits from sophisticated companies and a skilled workforce. But workers are not rewarded for building their own businesses.

We believe in building. Building is a solution to many of Ireland’s most pressing problems, from expensive housing to political polarisation, climate change and quality of life.

We believe in openness. In the past, Ireland reinvented itself by borrowing and copying ideas from around the world. This continues to be a good strategy.

We believe in the state. To build the best version of Ireland we will need a renewed state with more ambition and more capabilities than today.

We believe in the market. To build the best version of Ireland we will need to draw on the resources and talents of all parts of society, from Ireland and overseas.

We believe in broadly-shared prosperity. Ireland has succeeded in the past by empowering ordinary citizens and workers. This is the right model.

Conclusion: A new Jerusalem

69 years ago, Ireland made the decision to face outwards to the world. It was a turning point in the country’s history.

Today we are living in Lemass and Whitaker’s country. It’s a modern, wealthy, and cosmopolitan place with much to commend it. But many people’s lives are not easy. It can be a tough place to get started in life, and a tough place to do excellent work.

Ireland’s new situation calls for a change in strategy. Ireland’s problems have changed. They aren’t the problems of poverty and scarcity any longer. They are the problems of success and growth. The problems of growth are fundamentally different from the problems of poverty. They require different solutions.

As before, the answers are to be found abroad. But the questions are different. Instead of “how do we build and run a transistor factory?”, we need to ask “how do we extend a city?” or “how do we build a network of cutting edge companies and funders?”

Ireland is blessed with many advantages: strong communities, high trust, low political polarisation, a vibrant culture and a beautiful environment. If it can learn from others how to get better at building, Ireland can have the highest living standards in the world.