The Department of Public Expenditure is holding an open consultation with the public. It’s soliciting feedback on how Irish infrastructure and construction might be sped up. The deadline for input is 5pm today, the 4th of July. The more submissions from the public in support of faster delivery, the better. To make a submission, click here.

Ireland can’t build fast enough to keep up with demand, and now there are shortages of many things. It would be great if we could build faster. The government would prefer it. But the pace of building is bottlenecked by legal constraints that are either wholly or partially outside the government’s control.

There are two categories of law that slow the pace of building. The planning system is one. The planning system we’ve built is complex, messy and slow. But it is, at least, our own system. It comes from acts of the Oireachtas. It can be amended and adapted.

The other big constraint on how quickly we can build is EU environmental law. The EU has created many rules that relate to building: the environmental impact assessment directive, the strategic environmental assessment directive, the birds directive, the habitats directive, and waste water treatment directives, the environmental noise directive, and the energy performance of buildings directive.

The way the process works is that the EU passes a directive. Then, national parliaments in EU states transpose the directives into law. If states fail to transpose EU directives in a timely manner, they get fined.

The Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) Directive is one example. An EIA is a process whereby information is gathered about the impact of a development on the environment. A report is the output of the EIA. The EIA Directive does not preclude development going ahead, even in the event of significant environmental impacts. What it does require is for those effects to be assessed and for the authorities to take account of them.

EIAs are material for building for three reasons. The first is that they cost money to prepare. For a notional 500 unit scheme they might cost anywhere from €20,000 to €200,000. Spread across 500 units, this is not a huge amount of money.

The second reasons EIAs matter is that they take time to prepare. Screening, scoping, surveying, writing and reviewing an EIA report could take between six and twelve months. All going well, the EIA process runs in parallel to design work and other pre-planning jobs and doesn’t add significant time to a project.

The third issue with EIAs is that they add complexity and risk. An EIA might find an environmental impact (like bats) that needs expensive mitigation ( bat roosts). An EIA might require seasonal surveys, which could add another year to the project. And EIA reports offer rich pickings for objectors. If there are technical errors with the gathering of an EIA, the whole planning permission is vulnerable to being judicially reviewed and quashed. For example, in 2020, Dublin City Council announced plans to build a 2.5km cycle lane along Strand Road in Sandymount, Dublin 4. In July 2021, the High Court quashed planning permission on the basis that the cycle lane counted as urban development and needed an EIA. In 2025, The Court of Appeal overturned the high court’s decision.

The Sandymount case illustrates a problem with EIAs. A tool which had ostensibly been made to limit the environmental impact of large development was being weaponised to stop small scale development with a strongly net positive environmental impact. Though the opponents of the cycle lane ultimately lost, the scheme was held up in the courts for almost five years.

All of which is to say that EIAs are important inputs into the price, quantity and rate of construction. “When is an EIA required, and when must there be an EIA screening” are important questions.

The EU’s EIA Directive recognised the fact that EIAs are onerous. It set thresholds for different types of development to establish when an EIA would be automatically needed, and when one might be needed. The thresholds relate to lengths of road, width of pressurised gas pipes, litres of water treated and the like. In the EU’s directive, automatic EIAs only kick in for projects that are pretty big: 20km of overhead transmission lines, 10km of four lane road, and so on. The EU is also clear that the EIA directive is limited in its scope, and intends to target only projects of a relatively large size: "Member States may set thresholds or criteria for the purpose of determining which of such projects should be subject to assessment on the basis of the significance of their environmental effects. Member States should not be required to examine projects below those thresholds or outside those criteria on a case-by-case basis."

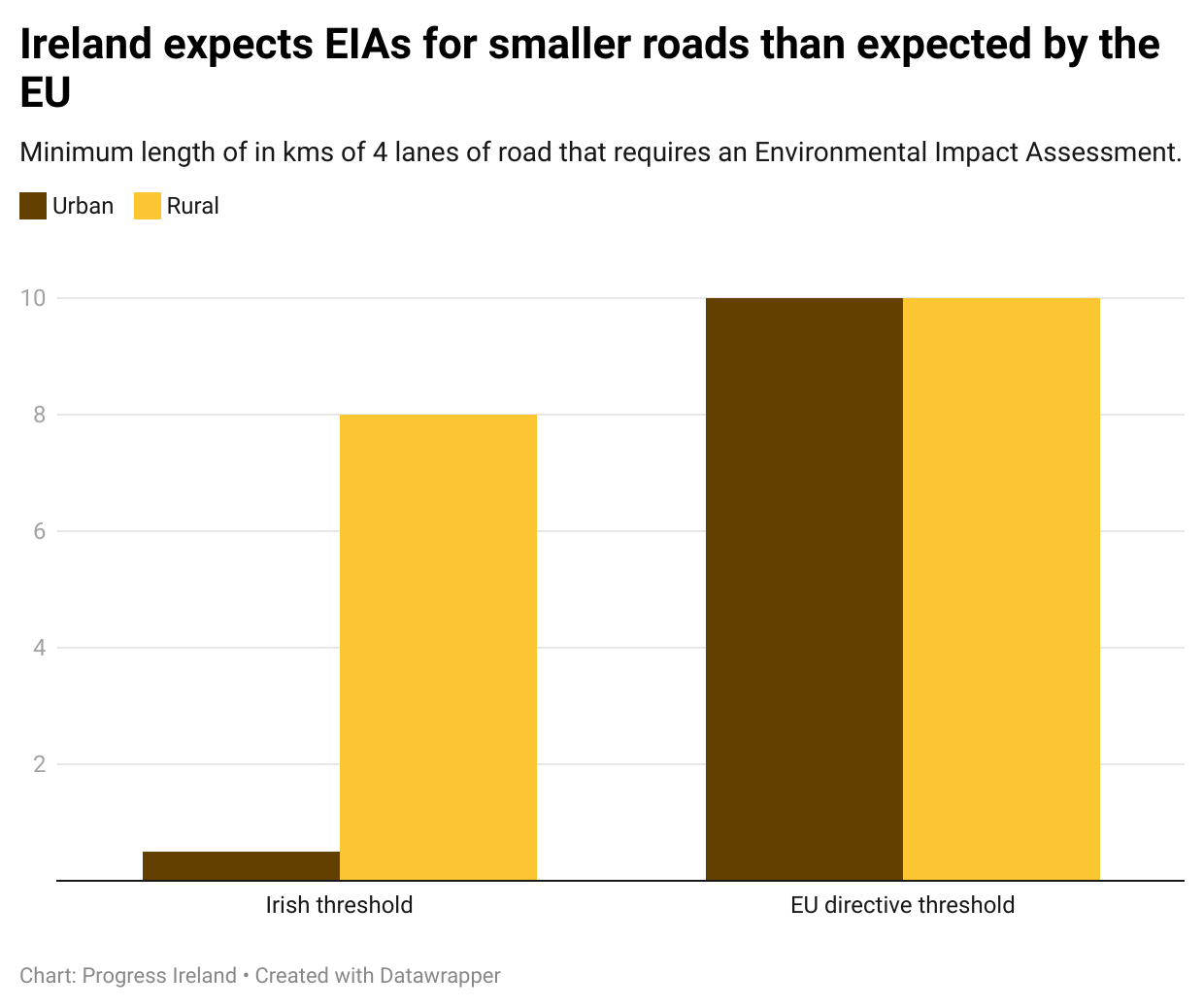

In transposing EU Environmental Impact Directives into law, the Irish government has in many cases gone further than expected by the EU. The way it does this is its choice of thresholds. Ireland demands an Environmental Impact Assessment for smaller developments than expected by the EU.

Take roads. The EU’s directive calls for an automatic EIA for roads of at least four lanes in width that are longer than 10km. In Ireland, an EIA must be produced for an urban road of four lanes in width and just 500 metres in length.

In Ireland, an EIA is also required if a road is widened to a width of four lanes – in order, for example, to introduce a bus lane. The EU expects an EIA for the construction of a fresh four lane road of 10km; Irish law expects an EIA for the addition of two lanes to an existing two lane road of 500 metres (in urban areas).

Wastewater treatment is another one. Irish Water owns some 1,400 wastewater treatment plants. The biggest one, at Ringsend, serves several hundred thousand people. A half a dozen serve more than a hundred thousand people. The rest of the 1,400 are small. The EU’s EIA directive mandates that large plants, serving more than 150,000 people, need an EIA. It says smaller plants should be screened for EIAs, but doesn’t set a specific threshold size. Ireland set the screening threshold at just 10,000 people.

Another problem with EIAs is their treatment by courts. One category of EIA is for the amorphous concept of urban development. What counts as a significant urban development, and therefore requires an EIA? As the Sandymount cycle lane shows, the Irish courts have at times taken an expansive view of this question.

Thresholds for EIAs will be reviewed as part of the new Planning and Development Act. The EIA thresholds for roads are to be found in a separate piece of legislation, the 1993 Roads Act. At a time of housing shortages, when legal complexity is strangling new development, the drafting around thresholds should be scrutinised carefully.