As a reader of this email, you are likely familiar with our national housing targets. The latest is 50,500 homes per year.

It’s hard to put this number in context. What do 50,500 homes look like? Is it too many? Too few?

One answer is that 50,500 homes look like Cork City. We need to build one Cork City this year, and next year, and the following year, for a couple of decades. Another answer is that it looks like building a new Dublin City every four years.

The construction of 50,500 homes per year isn’t something that can be achieved by building here and there, on odd plots of land. Building that many homes demands massive ambition, planning and forward investment.

Take City Edge, for example. City Edge is (by Irish standards) an ambitious plan to turn 300 hectares of industrial land in West Dublin into high density masterplanned housing. The City Edge plan is expected to take 45 years. By 2070, it’ll have contributed 40,000 homes in total. That’s about 900 homes per year, or 1.7 per cent of our annual target. Or take Cherrywood. Cherrywood is the biggest Strategic Development Zone in the history of the state. It’s ten years in the making. When completed in the late 2020s, it’ll have yielded… 10,500 homes.

All of which is to say, we need a bigger plan for where we’re going to put all these houses.

The two paths

When it comes to building new neighbourhoods, there are two options. We can build around roads or build around rail.

Building around roads is a somewhat underrated idea in Ireland (in that it’s so unpopular). But building around roads is a perfectly reasonable strategy. It can work. Cities of ten million people are built around roads and they work pretty well.

But we’d have to really commit to the idea. We’d need to bulldoze neighbourhoods to build giant 12 lane tolled motorways. We’d need ring roads upon ring roads. Suburban retail parks. Drive through banks. The whole nine yards.

I don’t think this is the path Ireland wants to follow. Irish people don’t love their cars as much as Texans. We have our climate targets. Successive governments wouldn’t make the investments.

The other option is to build around rail. Rail has some nice features: it has a huge carrying capacity (about 50x the equivalent width of roadway), so it doesn’t take up much space. It naturally lends itself to pleasant, walkable, sustainable, mixed use urbanism. Builders like it because it enables very dense developments. Rail companies like lots of buildings near their lines because they provide passengers for the trains.

The problem with rail is that it’s hard to build. It takes a lot of coordination, ambition, foresight, and technical skill. I don’t need to labour this point. Metrolink’s 12 kilometres of tunnel is nearly 20 years in the making.

There is a way, though, to get much of the benefits of a metro system with much less effort, investment and risk. It could unlock a giant city-spanning train network with the capacity of a metro, some 78 kilometres in length. The network would enable much greater density within the city and open up 15 kilometres of green fields, on which some 135,000 houses could be built right away.

The main thing we’d need to build is one short tunnel, 3.5 kilometres in length.

An S-bahn

This is an idea borrowed from 1930s Germany. Berlin at the time was congested. It sat at the centre of a spider’s web of rail lines. But the rail lines weren’t designed to connect the city of Berlin; they were designed to connect the hinterland to the city of Berlin. The rail lines terminated at the edge of the city at northern, southern, eastern and western termini.

Berlin’s idea was to connect the northern and southern rail termini with a tunnel. This had three main benefits. First, it allowed travellers from the north to go to destinations in the south and vice versa. Second, it created new stations in the centre of the city, along the tunnel’s route. Third, it allowed trains to run at a much greater frequency, because they didn’t need to be turned around at the city terminus. These things came to be known as Stadtschnellbahns, or S-bahns for short.

This idea worked. It was copied by: Bremen, Dresden, Hamburg, Hanover, Magdeburg, Leipzig-Halle, Munich, Nuremberg, Frankfurt, Mannheim, the Rhein-Ruhr Metropolitan Region, Rostock, Stuttgart, Vienna, Zurich, Milan, Stockholm, Prague, Copenhagen, Rotterdam, Paris, Stockholm, London and Melbourne. Among other cities.

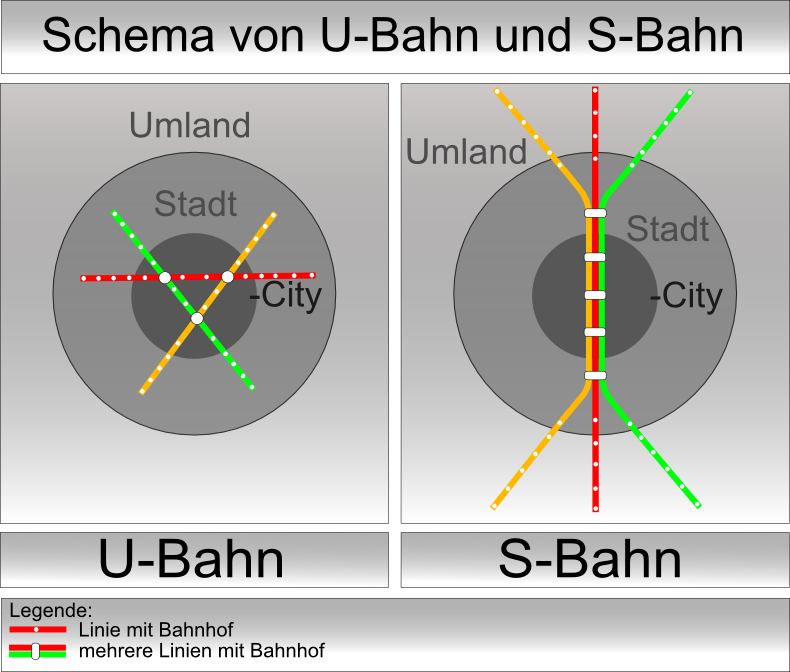

The following graphic (in German, but decipherable) does a good job of depicting S-bahns’ strengths and weaknesses. They are good at connecting the city to the hinterland, but not as good at connecting locations within the city as a normal metro system. They also require much less tunnelling and thus, are cheaper to build.

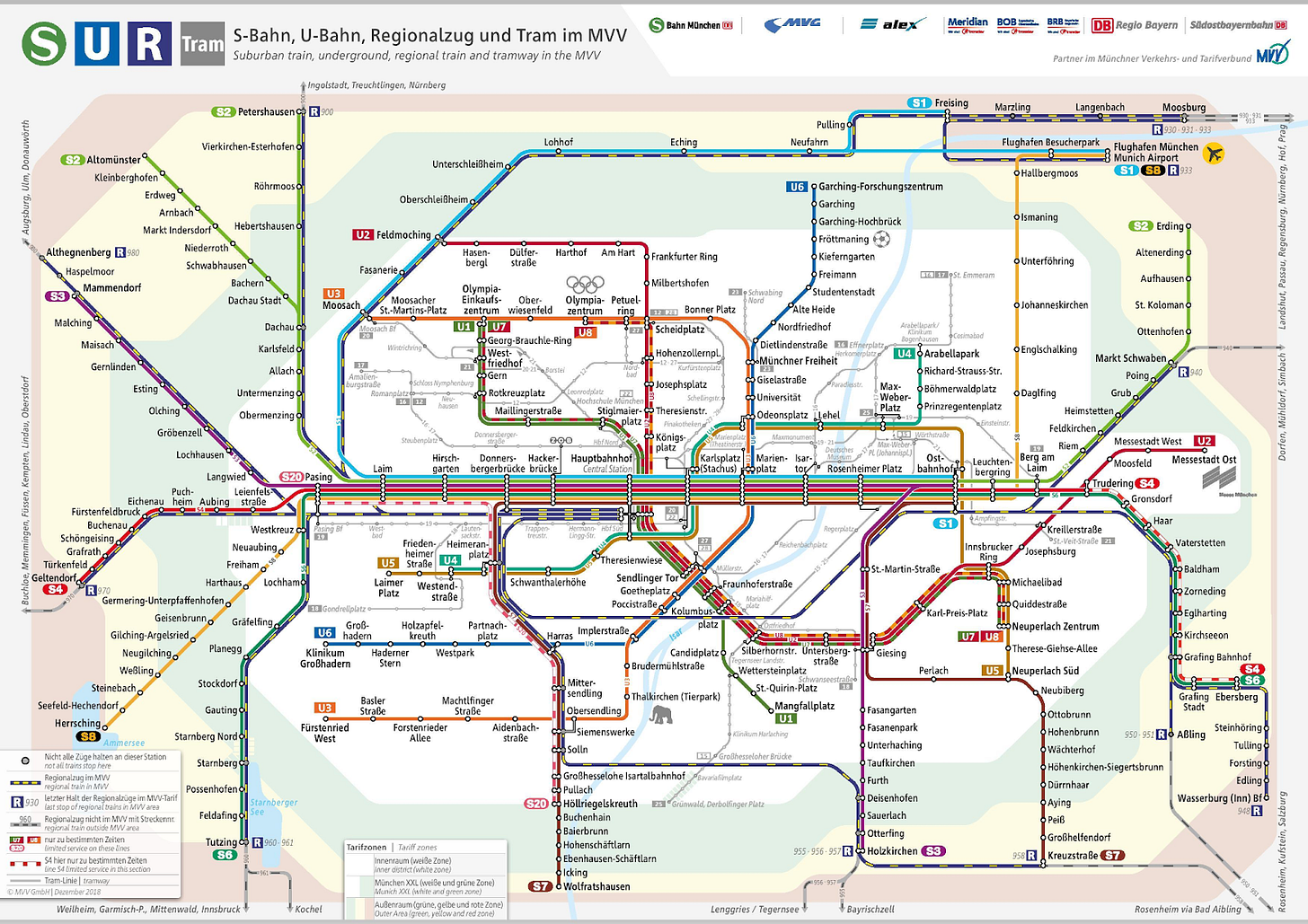

The following map is of Munich’s commuter rail system. Note the thick trunk at the centre of the network. This is the tunnel. Almost all lines converge on it. It connects the big stations at the west and east of the city, and runs through the city centre.

S-bahns make sense in Europe because European cities have a legacy of heavy rail. Where once the cities needed trains to deliver raw materials and goods, now they need trains to move people around the metropolitan area. Modern S-bahns repurpose industrial rail as electrified, high capacity people movers.

Dublin is a fine candidate for the S-bahn treatment.

A plan

We should build a 3.5 kilometre tunnel linking Connolly and Heuston. The tunnel would let people travel from the west to the east, the east to the west, the west to the centre, and the east to the centre.

By segregating this system from intercity services, giving it dedicated lines, we could massively increase its capacity. (This is the problem with the existing Phoenix Park tunnel – it is shared with intercity services, which greatly limits its capacity.)

Capacity matters because, circling back to the beginning, we need places to build houses. When you’re seeking to build say 200,000 homes in Dublin over ten years, the bottleneck is transport capacity. The greater the capacity of the commuter rail system, the more homes can be built.

Irish transit heads will recognise this idea. It’s a first cousin of the DART+ project, which was considered at length before being shelved in 2021.

Besides all the standard arguments for building an S-bahn in a congested city, in Dublin, there’s one further sweetener: there are 15 kilometres of empty green fields directly west of Dublin, between Adamstown and Sallins. That stretch of land is Dublin’s single best opportunity to alleviate its housing shortage.

How many homes could be built there? The idea is to build homes within a five minute walk of the station, so that rail transport is genuinely convenient. That’s about an 800 metre radius, which comes to 201 hectares. I interviewed an expert on Transit Oriented Development, Professor John Renne, about this in a piece in The Currency. Prof Renne said “To justify having a train station, you need a minimum of 4,000 households [within 800 metres of the station]. On the medium side, it’s around 12,000-15,000. And on the maximum side, you’re talking about maybe a central downtown location or a really intense area, you would be looking at upwards of 25 to 30,000 units within 800 metres.”

For west Dublin, let’s assume 15,000 homes within 800 metres of the station. Along the 15 kilometre line, there’s room for nine stations. That means there’s room for about 135,000 homes within walking distance of a station.

The goal would be for this to be a new business and cultural quarter of the city, as opposed to simply a dormitory suburb. It should be a place to live, work, shop and relax. Both because nice places are nice in themselves, and because it’s more efficient for the trains to be full in each direction throughout the day. We don’t want everyone going east in the morning and west in the evening. Professor Renne said: “Generally, you need a really strong employment base. So it’s not just the 12 or 15,000, or 20,000 households near the station, but it gets into the number of jobs nearby also. You’d probably want to see at least half that number — or more — of jobs.”

135,000 homes in a new quarter of Dublin would be a good start. But building the tunnel, and the network, would enable so much more housing than that. The capacity and usefulness of the entire 78 kilometre DART network would be massively upgraded, along with the potential for new housing along those lines. A bigger more capacious network would allow the whole city to densify naturally.

To be sure, a Dublin S-bahn would not be a simple project. The final five kilometres of rail leading to Heuston Station are currently single tracked; they would need to be widened. The whole line would need to be electrified. To keep the network segregated from intercity lines (and thus, unlock more capacity) the trains to Wicklow and Wexford might get the chop. Either that or the track would need to be widened the whole way through south Dublin. Building out roads, water, schools and so on for this new city quarter would not be trivial.

But these problems are solvable. We have started to build the tools we’d need for this job. Urban development zones, which are part of the new planning act, are a perfect tool for masterplanning new neighbourhoods. If we paired UDZs with land readjustment, we could get the landowners on board.

Land value uplift along the Adamstown–Sallins corridor could pay for much of the tunnelling and other capex. Assuming €12 million per hectare uplift on net-developable land, 80 per cent of gross catchments redevelopable, and a 33 per cent capture rate, the discounted value the could be captured by the state is around €4 billion. (How to capture the value? Again, land readjustment).

However one looks at it — number of homes unlocked, cost efficiency, carbon efficiency, pleasantness of new places, cost to exchequer, commute minimisation — this would seem to be the best investment we could make in the future of the city.

And when we’re done we can do something similar in Drogheda, Limerick Junction, Cork, Limerick, Galway and Waterford.