A common narrative about environmental regulation in Ireland is that the biggest problem is goldplating. In other words, Ireland is adding lots of burdensome requirements on top of European environmental directives. But the reality is that even when these extra requirements are stripped away, the underlying directive makes it hard to build things.

EU Directives are pieces of legislation approved by the European Parliament and the Council of the EU. It’s up to the 27 member states to “transpose” them into domestic laws. One way transposition can go wrong is in the degree of compliance, with member states either under- or over-complying.

Under-complying means you might leave something out, in which case the EU will begin infringement proceedings. Ireland has been in trouble over the Water Framework Directive, for example.

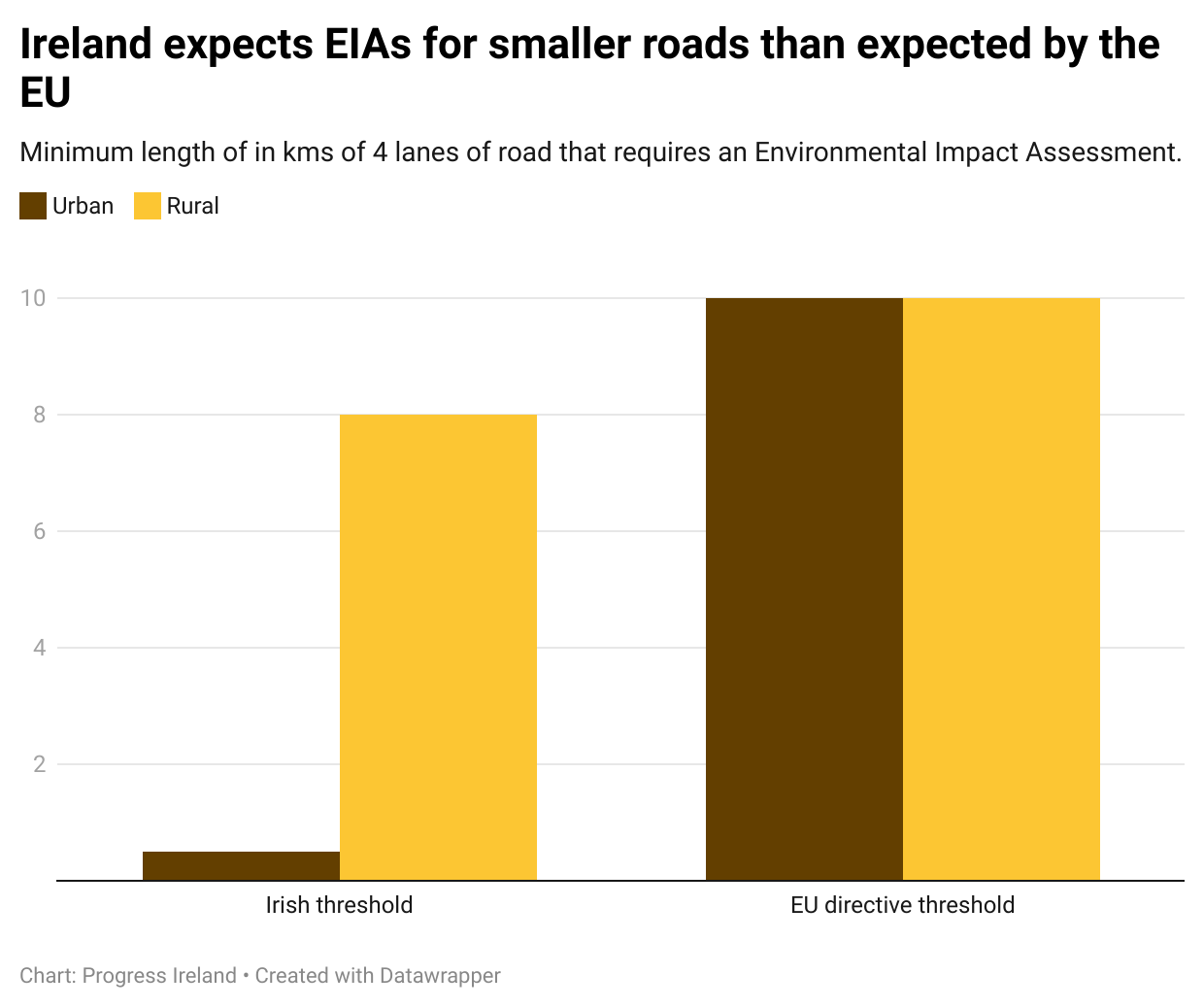

Over-compliance, or goldplating, means you may add extra conditions or processes. An example is the threshold for environmental impact assessments (EIAs), as previously examined by Progress Ireland:

Another example from the same article is EIAs for waste water treatment plants. The EU mandates that large plants, serving more than 150,000 people, need an EIA, while smaller plants need only be screened to see if an EIA is needed. Meanwhile, Ireland makes EIAs mandatory when plants serve just 10,000 people.

In many ways, Ireland is guilty of over-compliance. But that doesn’t mean that perfect compliance leads to perfect outcomes. The minimum implementation of EU environmental directives – and the relevant case law – is onerous in all sorts of unnecessary ways that it doesn’t need to be. To understand how, let’s examine some relevant directives in turn below.

Environmental Impact Assessments

Take EIAs, which are mandated by the EU for certain planning decisions. They have a common sense and reasonable purpose: it’s important to understand the environmental impact of development and make that information part of the decision making process. If a new development will damage nearby water quality or destroy nesting grounds for a rare species of bird, it is perfectly reasonable (and desirable) that those effects are known and ideally mitigated or averted.

The EIA Directive (2011/92/EU, as amended by 2014/52/EU) has a number of key provisions. Crucially, there is a long list of projects (Annex I) which must have an EIA before they can be approved by a planning body. There is a minimum consultation period for citizens of thirty days. Planning consent must be accompanied by monitoring and/or mitigation where appropriate. Members of the public must be able to appeal to the courts or another neutral body in order to review these decisions. This is what the directive itself says, not what any member state has added on top.

As with all regulations, we should judge it by its effects, not its intentions. What are the effects of the EIA directive? Are they disproportionate?

First, EIAs are a significant factor in planning delays. The Draghi report decried a “lengthy and uncertain permitting process for new power supply and grids”. EIAs contribute to this, taking an average of 30 months – two and a half years – to prepare and complete, across all EU countries.

EIAs are extremely complex, and planning decisions based on them can be judicially reviewed (under Article 11 of the directive, and the Aarhus Convention). Even decisions not to screen for an EIA, or not to carry one out after screening, can be judicially reviewed, as the court found in Gruber (C-570/13). This adds more delays to an already slow process.

A project may have some environmental costs. But there are costs associated with not pursuing a project. The social, economic, and climate benefits can be significant too: stronger economies, increased energy security, and lower emissions. Prolonged EIAs mean that these benefits are more costly to access, or sometimes mean that we don’t get them at all.

This isn’t to argue that environmental damage is fine. It should be mitigated, as required by the EIA Directive and other EU Directives. (More on this in the next section.) The current EIA Directive does allow development where there are ‘significant adverse effects’ if mitigation/monitoring steps are taken, where appropriate (Article 8a).

The EU has already recognised the importance of some projects and the resulting need to ease their permitting. A more recent EU regulation includes stricter time limits for the approval of renewables, and the derogation of EIAs in a limited set of cases. EIAs shouldn’t simply be scrapped — we need environmental assessments as part of the planning process. But efforts should be made to streamline them and ensure that they don’t unnecessarily hinder development.

Birds and Habitats Directives

It’s a similar story when it comes to the Birds and Habitats Directives (Directives 2009/147/EC and 92/43/EEC respectively). It makes sense to have protections for endangered species and important habitats in Europe. However, as currently constituted, the directives have some problems.

First, one way to address any negative impact from a development is to mitigate the problem somewhere else, offsite. For example, if some newts will be harmed by a new housing project, you could support newt populations elsewhere by enhancing habitats or supporting breeding programs. This can offset the impact of the development.

But Article 6(3) of the Habitats Directive states that consent can be given to a project “only after having ascertained that it will not adversely affect the integrity of the site concerned”. And the judgement in Briels (C-521/12) states that offsite mitigation “cannot be taken into account in the assessment of the implications of the project provided for in Article 6(3).” The result is that offsite measures fall under Article 6(4), and the project can only proceed if alternatives are examined and it’s in the “overriding public interest”. If the site in question hosts an important habitat or species, then only human health, public safety, or environmental concerns can be used to justify approving the project. Otherwise it has to get approval from the EU Commission.

In other words, if you try to mitigate offsite – a common sense way to minimise environmental impact while still pursuing a project – things become very complicated very quickly, and much slower.

On site mitigation is a problem because it can be incredibly expensive to protect species and habitats on the site you’re developing. Consider the £120 million bat tunnel in England, built to (potentially) save around 300 bats, at a cost of £330,000 per bat. That is the most extreme example of how onsite mitigation can go wrong. Most projects don’t have the budget and political importance of HS2, so when faced with high mitigation costs, they simply don’t happen. Investment and jobs do not materialise.

Second, many species are protected at the EU-level even if they’re locally abundant. The Birds Directive states that it applies to “all species of naturally occurring birds[…] their eggs, nests and habitats” (Article 1); and members states “shall… establish a general system of protection for all species of birds” (Article 5). The Habitats Directive mandates the creation of “a system of strict protection… in their natural range,” including bans on “deterioration or destruction of breeding sites or resting places.” (Article 12).

For example, all bats are protected throughout the EU (Annex IV, “MICROCHIROPTERA”), even though several species are common in Ireland. The common pipistrelle and the soprano pipistrelle each number in the millions, while Leisler’s bats number in the hundreds of thousands. Common sense tells us that these bats don’t need this level of protection in Ireland.

Aarhus

The Aarhus Convention is perhaps the most interesting case when it comes to goldplating. It’s an international treaty, with three key rights: access to information, public participation, and access to justice. It was adopted by the EU primarily via two separate directives: 2003/4/EC and 2003/35/EC.

The access to justice provision is the pertinent one when it comes to goldplating. There are two relevant aspects: standing (who gets to challenge planning decisions), and associated costs.

First, standing. Article 3 defines the public concerned as: “the public affected… or having an interest in, the environmental decision-making procedures [and] non-governmental organisations promoting environmental protection”. This gives environmental NGOs the ability to take cases to court, as well as members of the public.

In other words, this directive gives broad standing to members of the public and NGOs to challenge planning decisions. They have the ability to force courts to review the environmental procedures used to reach a planning decision, and establish whether these were done lawfully. If you think that judicial reviews should only be brought by nearby residents (who have a legitimate interest in a proposed development) and NGOs restricted, this isn’t allowed. The directive rules NGOs in.

These rules on standing asymmetrically favours complainants when it comes to development decisions, as those proposing a development already have standing. The broad understanding of standing means that there are many people and groups who have the right to bring a case, making it more likely that one of them will do so.

Reviewing decisions sounds innocuous, but when done repeatedly it has a series of negative consequences. Projects slow down or even stop while court proceedings take place, increasing costs. For instance, activists attempted to block €3 billion of wind farms in Spain, benefitting from standing granted under a Spanish law which transposes the access to justice principle of Aarhus. Similarly, the Fehmarnbelt fixed link in Germany was challenged under the Environmental Appeals Act (Umwelt-Rechtsbehelfsgesetz), which transposes the access to justice principle of Aarhus into German national law. Judicial reviews are so commonplace in Ireland that they were expected to delay Dublin’s long overdue metro system before the original planning decision had even taken place.

More resources for courts could help, but this would be to treat the symptoms rather than the underlying problem: projects being forced through the courts to a disproportionate degree, even after they’ve already been approved. This can make development unprofitable, or simply unattractive – who wants to be arguing in court and paying lawyers for months or years on end?

Environmental impact assessments, the focus of many judicial reviews, are complex and technical, so it’s easy for a developer or a local planner to make a minor mistake when carrying them out or making a decision based on them. In Ireland this can be enough to invalidate the entire planning permission after a judicial review.

There are a few ways that the bad parts of this law could be minimised. Spain handles appeals much better than Ireland, for example. However, some solutions have been ruled out by the European courts.

For instance, you could set a membership threshold so that an organisation bringing a claim has to have some kind of broad legitimacy. High thresholds are not allowed, however: in Djurgården (C-263/08), the court rejected a 2,000-member requirement as contrary to the EIA Article 11 and Aarhus objective of wide access.

Or you could limit appeals by NGOs to those who had already participated in the earlier stage of the relevant part of a planning process. That would prevent nuisance cases from parties who only get involved opportunistically once planning permission is initially granted. However, this isn’t allowed either: in Stichting Varkens in Nood (C-826/18), the court stated that NGOs cannot be refused court access because they didn’t submit comments earlier.

The second aspect is who bears the cost of these legal challenges. Access to these challenges must not be “prohibitively expensive”.

This is quite vague. There is some case law explaining it: the court in Edwards (C-260/11) stated that all costs should be covered “as a whole” (including potential adverse costs if an applicant loses the case). There should be a specific check of whether a claimant can pay the necessary costs, and a review of the overall reasonableness of the standard. The Commission’s 2017 Notice states that national governments must provide clarity on costs in advance so that litigation is genuinely affordable.

None of this spells out a specific cap on what applicants must pay, but it’s going to have to be low, predictable, and meanwhile the government has to cover all other costs. Some countries, like the UK, do this via a cost cap. This is perhaps a worst case scenario, because it means that the cost of challenging development decisions doesn’t scale as the appeal drags on.

Others do this by having an own-cost rule, so that applications for judicial review have to pay their legal costs (and aren’t liable to pay the other side’s costs if they lose). This is better than a mere cap. However, it still reduces the cost of judicial review dramatically from what it might be, especially if the applicant faces a high risk of losing, when they might normally pay everyone’s legal costs.

And as long as motivated individuals and NGOs have standing, cost caps are only a partial deterrent to them blocking projects via judicial reviews. Some of them have very deep pockets, or can find lawyers who will work on a pro bono basis.

The best of Europe was built before we had Aarhus. Do we need these wide standing and cost protections today?

A better way

I’ve previously written in more detail about some of the available reforms, such as centralised mitigation; replacing continent-wide species protection with local decision-making; prioritising green projects, energy security, and national infrastructure by exempting them from EIAs; and raising the bar for judicial review, or even removing judicial review altogether, allowing environmental issues to be decided by lower courts with no special grounds for appeal.

Goldplating is a problem, but so are the actual directives. We should enact reforms in Brussels and in member states so we can have both economic growth and environmental protection.

If you’d like to discuss EU environmental directives and their impact on competitiveness, you can reach me at fergus@progressireland.org, on LinkedIn, or on X.