It might be that Irish people don’t care much about investment taxes. But they certainly care about housing.

I’ve written before about how Ireland’s high investment taxes squeeze startups. It’s the same thing with housing. High taxes on investment kill housing projects and drive up housing costs.

Ireland has low corporation taxes, it’s true. But low corporation taxes are not the same thing as low investment taxes. There is more to investment taxes than corporation taxes.

Investors (mainly) get taxed at three points. They get taxed when the company makes a profit (corporation tax). Then get taxed when they take money out of the company (dividend tax) or when they sell the company (capital gains tax).

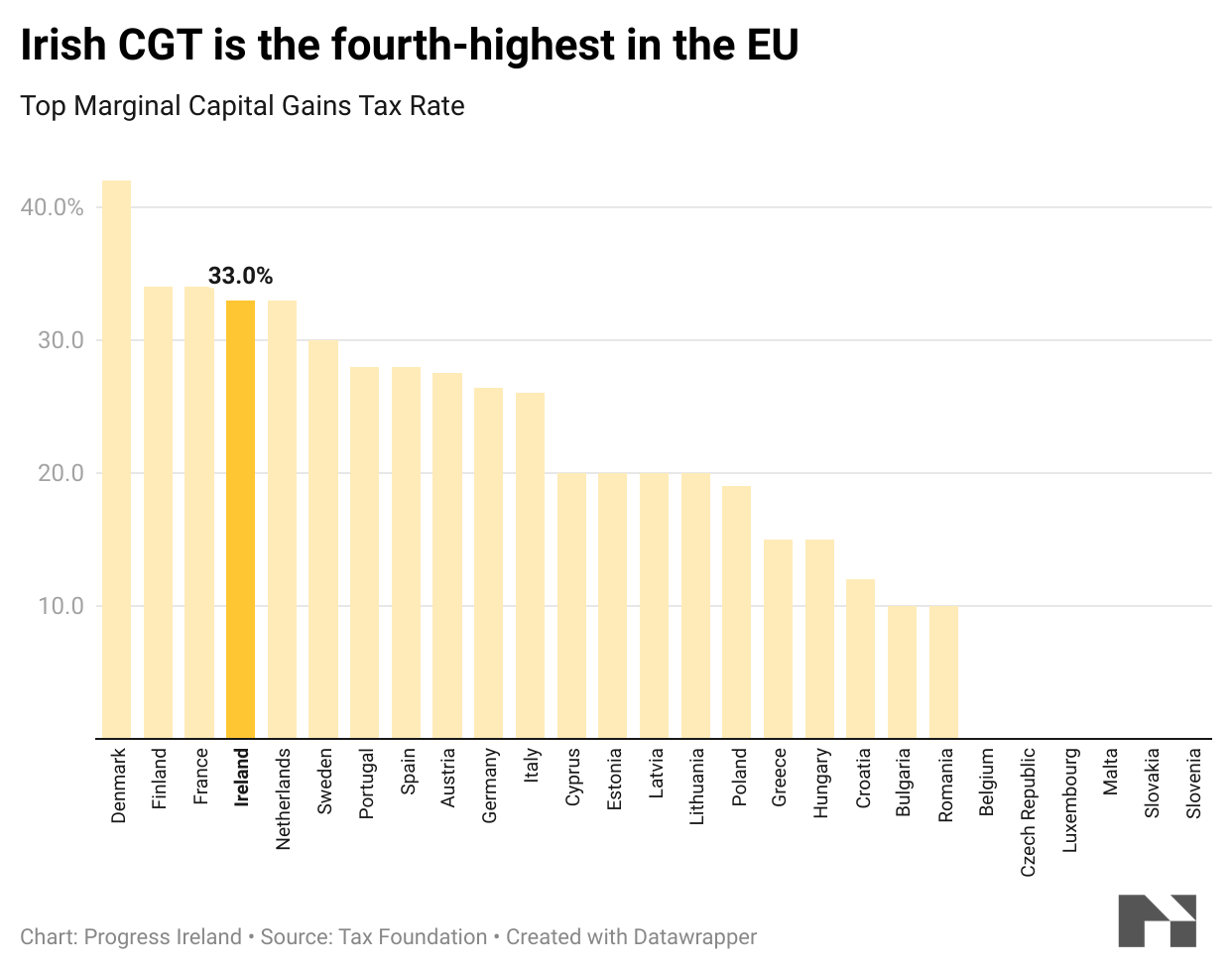

In Ireland, taxes on profits are low. But the other two types of investor taxes are high. Capital gains taxes are the fourth highest in the EU:

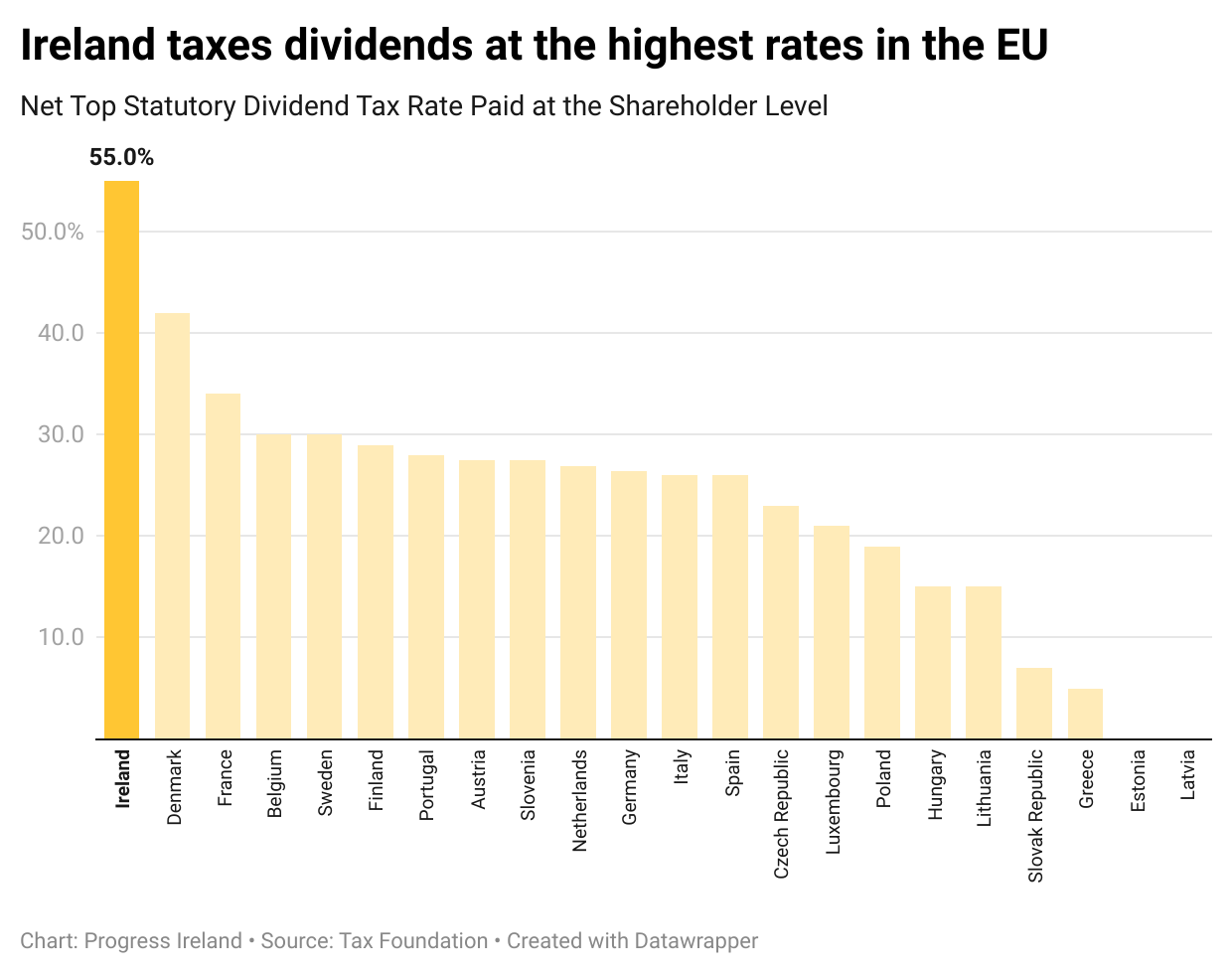

And Irelands dividend taxes are the highest in the EU. Including USC, high earners pay a combined 55 per cent in dividend tax. High taxes on dividends hurt investors two ways: directly, by reducing the value of dividends; and indirectly by reducing the value of the company when it’s time to sell it.

The price of risk

I’ll back up a bit. Why do profits exist? What’s their social purpose?

Profit is the price of risk. The greater the risk of investors losing their capital, the more profit they will charge. Low risk projects, like lending money to the government, will generate a small expected profit of two to three per cent per year. Medium risk ones, like buying a house to rent it out, will generate a profit of around ten per cent per year. And high risk ones, like building data centres in space, will be expected to generate profits of 30-50 per cent per year.

The development of new apartments is at the riskier end of the spectrum. Lots can go wrong: The bottom might fall out of the housing market during construction; the scheme might get JR’d; construction costs might rise; interest rates might rise. In compensation, investors will expect to make about 15 per cent on the money they have staked in the project, per year. Another term for this is a hurdle rate. A hurdle rate is the expected return a project must surmount to go ahead.

There are lots of ways to define profit. Developers will sometimes use gross profit, or percentage of gross development value. The one I want to focus on is a metric called internal rate of return, or IRR. IRR shows how much profit is made, per year, after tax, as a percentage of the money invested into the project. It allows for apples-to-apples comparisons between different types of project. Housing investors will target an IRR of about 15 per cent per year.

Imagine a scheme to build a block of apartments. The project is expected to take five years from start to finish. It’ll cost €30 million between the land and construction cost. To generate an IRR of 15 per cent, it will need to sell for €60 million in 2030. €60 million is the magic number. If the block looks like it’ll sell for €60 million or more, it’ll go ahead. If it looks like selling for €59 million or less, it won’t.

In Ireland we have a problem with apartments. We can’t build them. For a few years, we built them in and around Dublin. Outside of Dublin, we haven’t built them since the Celtic Tiger days. And now, we don’t build them anywhere.

Why is this? One way of answering is that they don’t generate a return big enough to compensate for the risks involved. Their IRR is lower than 15 per cent.

Why don’t they generate an IRR of 15 per cent? A lot goes into this: higher construction costs, greater planning delays and risk, higher cost of capital. But one element is tax.

How Irish investment taxes impact housing

I’ve talked about investment taxes — corporation tax, dividend tax and CGT — and also about IRRs. How do they fit together? Specifically, how do taxes impact IRRs?

The first step is to imagine a standard apartment development project. I imagined a project that ran for five years. It was 70 per cent funded by borrowing and 30 per cent by equity. I assumed the interest rate for the loan was six per cent and was repaid at exit.

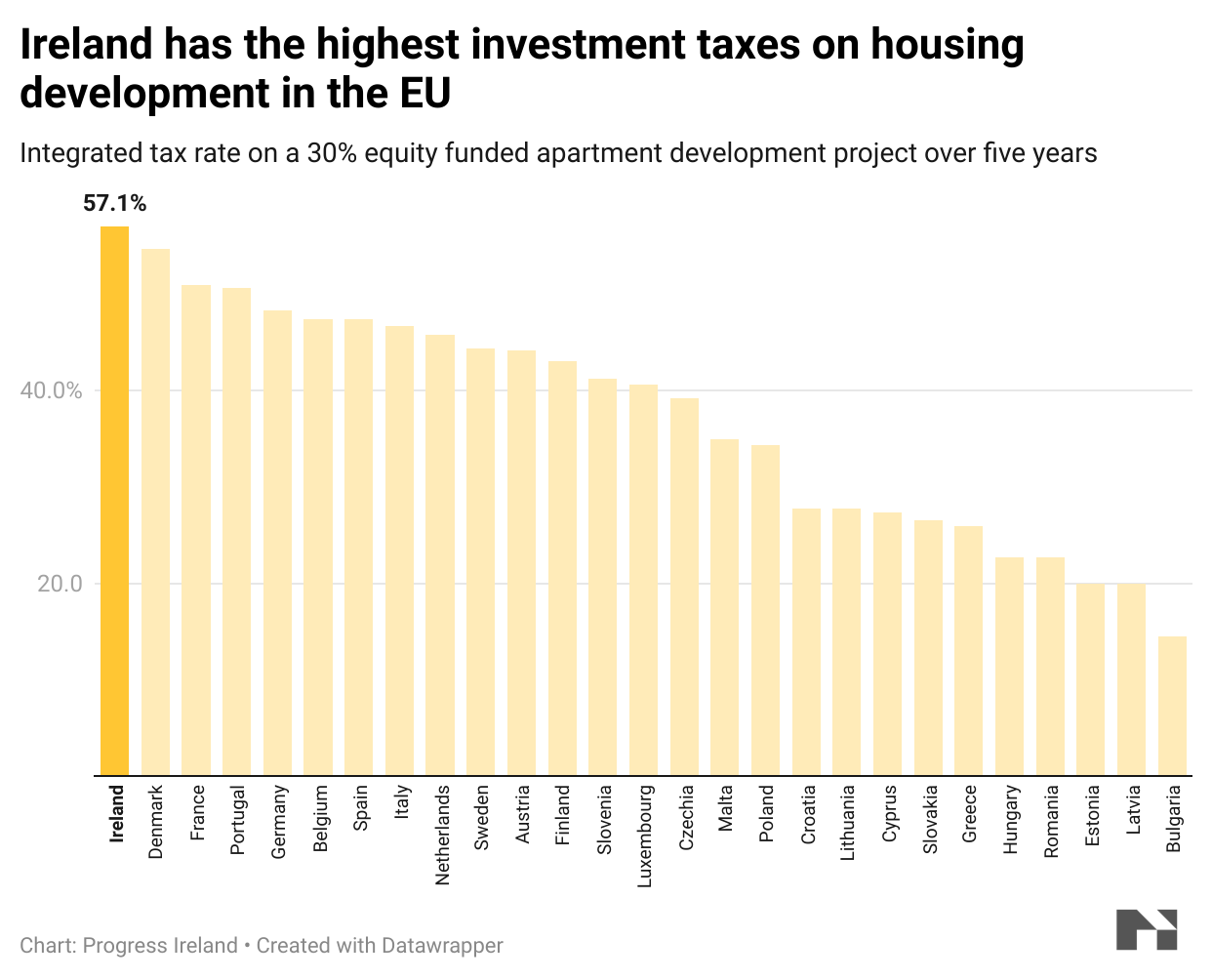

Once I had a specific type of project in mind, I could integrate the three main types of investment tax into one number. The calculation is very simple: it shows the layers of tax a euro must go through before it ends up in an investors’ hands. The two layers of tax are corporation tax and dividend tax.

Why not CGT? Most property developers don’t take cash out in the form of dividends. Instead they usually roll profits up in the company and use it to build another project. All going well, they eventually cash out by selling the company. So why does my model focus on dividends? I focus on dividends because the value of the company is itself derived from its dividend stream. Higher taxes on dividends mechanically lower the value of companies. So in the end, it all comes back to dividends.

The upshot of all this is that Ireland has the highest integrated tax on housing developments in the EU, at 57 per cent.

I want to understand how taxes feed through to IRRs, hurdle rates and ultimately the number of projects that go ahead. Having worked out the integrated tax rate for a housing project, the second step is to work out what it means for IRRs. I want to bring everything back to IRRs because they’re the universal, apples-to-apples metric that tells us what projects should get funded.

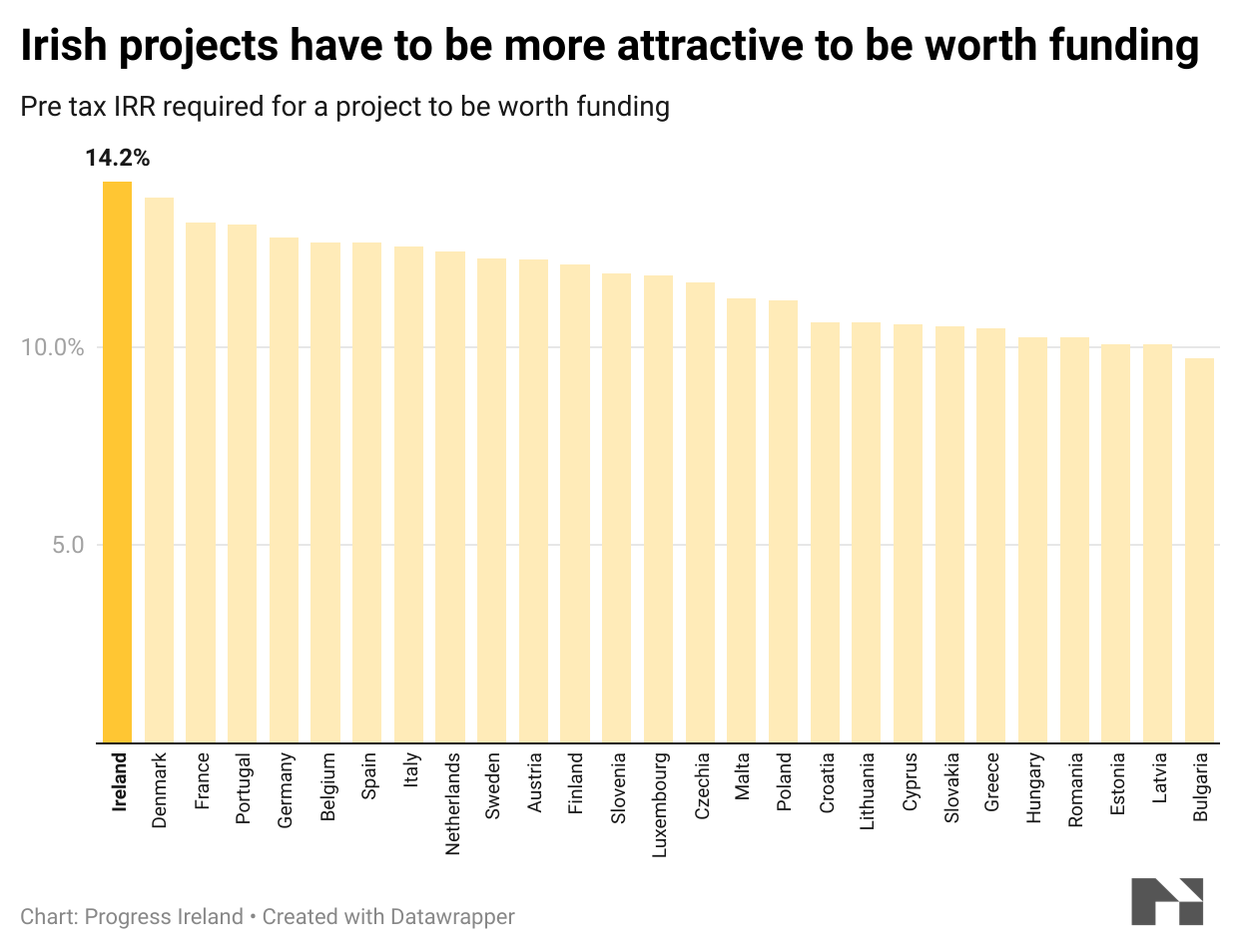

The way I do it is by asking “How good does a project have to be, before tax, in this country, so that equity investors still get their target 15% after-tax IRR?” (Given our starting assumptions of 70 per cent debt funding, six per cent interest, a five year project.) The number this generates I’ve called a Pre-tax hurdle IRR.

You might be wondering — if this number is the pre-tax IRR required for a project to go ahead, and the post-tax target IRR is 15 per cent, why is the pre tax target lower than 15? The answer is that I’ve assumed the project is funded 70 per cent by debt. Debt amplifies returns to equity investors. So a Swedish project whose pre-tax IRR is 12.3 per cent can make 15 per cent for investors after tax, once debt is applied.

To be sure, the burden of investment taxes don’t fall solely on investors. Other sectors — land, non-corporates, and labour — carry some of the burden. More on the incidence of corporate taxes in the New Year.

What’s the takeaway?

I’ve created an integrated tax rate for a building project, and shown how it differs between EU countries. And I’ve shown how the integrated tax rate changes hurdle rates. How does the hurdle rate change the number of apartments built?

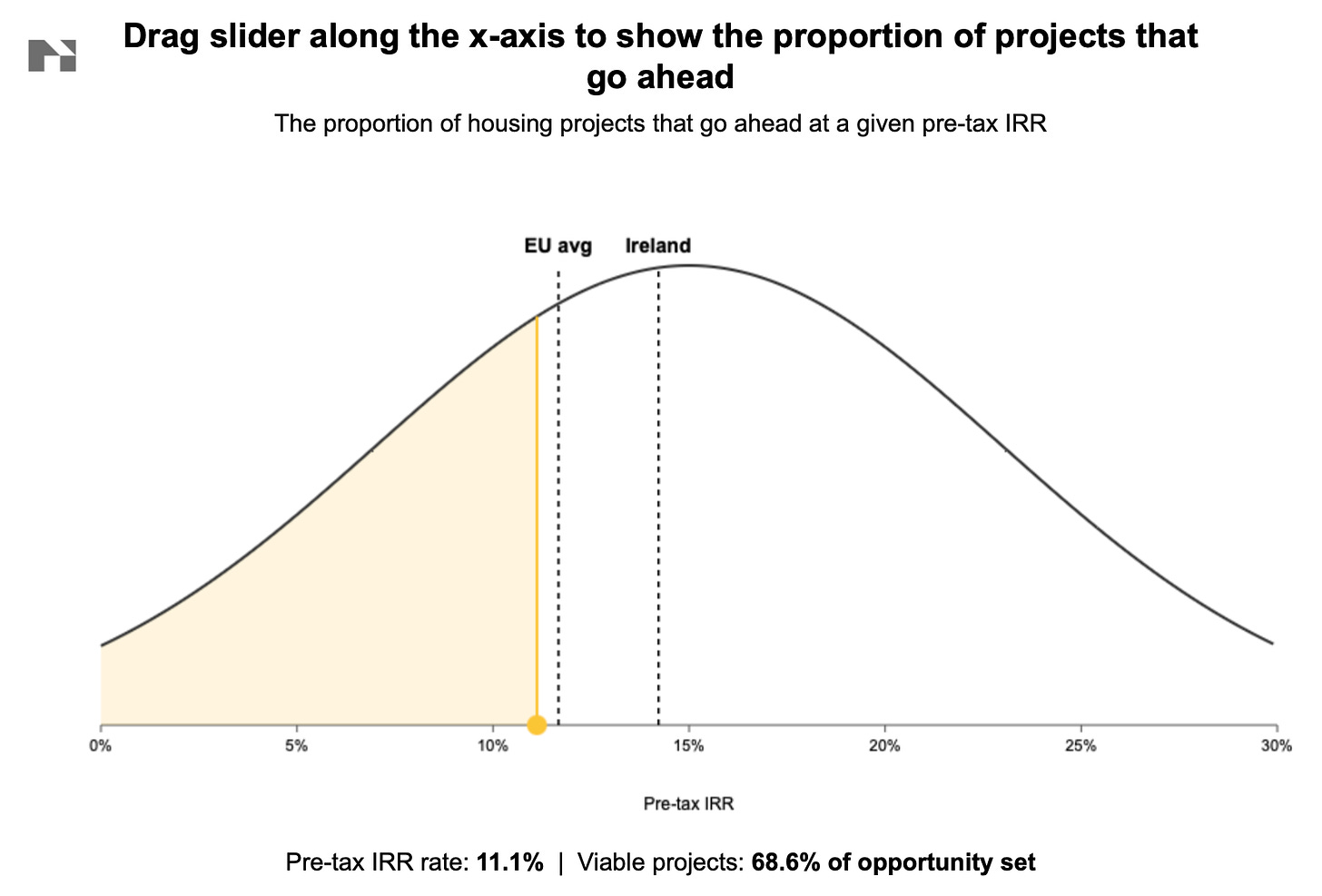

To answer this, I’ve had to make some assumptions. I’m assuming a normal distribution of potential projects with an average pre tax IRR of 15 per cent. I’m assuming a standard deviation (ie, how tightly the projects are clustered around the average) of eight per cent. The standard deviation number is admittedly a finger in the air job.

I’ve made a toy model to show how hurdle rates feed through to projects. As a result of high investment taxes, hurdle rates in Ireland are higher than the EU average. In this model, only 53 per cent of potential Irish projects are viable in this model, compared to 66 per cent of EU ones.

It might be that Irish people don’t care much about investment taxes. But they certainly care about housing.