In the late 19th century, only 3 per cent of Irish farmers owned the land they worked and lived on. Today, some commentators are concerned that those days are returning. Their fear is that Ireland is being turned into a “nation of renters”.

Today, I want to discuss this concern. Would it be bad if it happened? Does the evidence support that it is happening? And, as the concern implies, are there too many rental properties in Ireland? I will answer: yes, no, and no.

Are low levels of homeownership bad?

The first thing to say is that there are good reasons for wanting to retain high levels of homeownership. The conventional argument for this is that homeowners have a “stake” in society.

What precisely having a “stake” means can be debated at the national level. But at the local level, there is a fairly straightforward model of why homeownership is important: it makes for nicer streets where the costs and benefits of maintenance are internalised. When people own a home, they have an incentive to see the street improved. Each owner-occupier has an incentive to provide positive externalities. This is because homes on a well-manucured and beautiful street are worth more (and, not unrelatedly, are more enjoyable to live on). Hence owner-occupiers have an incentive to plant nice flowers, keep up on maintenance, and so on. This basic model is one reason why planning and zoning restrictions emerged in the first place.

On top of this all of the traditional arguments apply: homeownership provides security of tenure, provides an investment vehicle, provides security in retirement, and increases equality.

All in all, a return to the 19th century norm of insecure tenancies seems like a bad outcome. So, this part of the concern sounds about right: if Ireland were to become ‘a nation of renters’ of that kind, then that would be bad at the margin.

But is Ireland becoming a nation of renters?

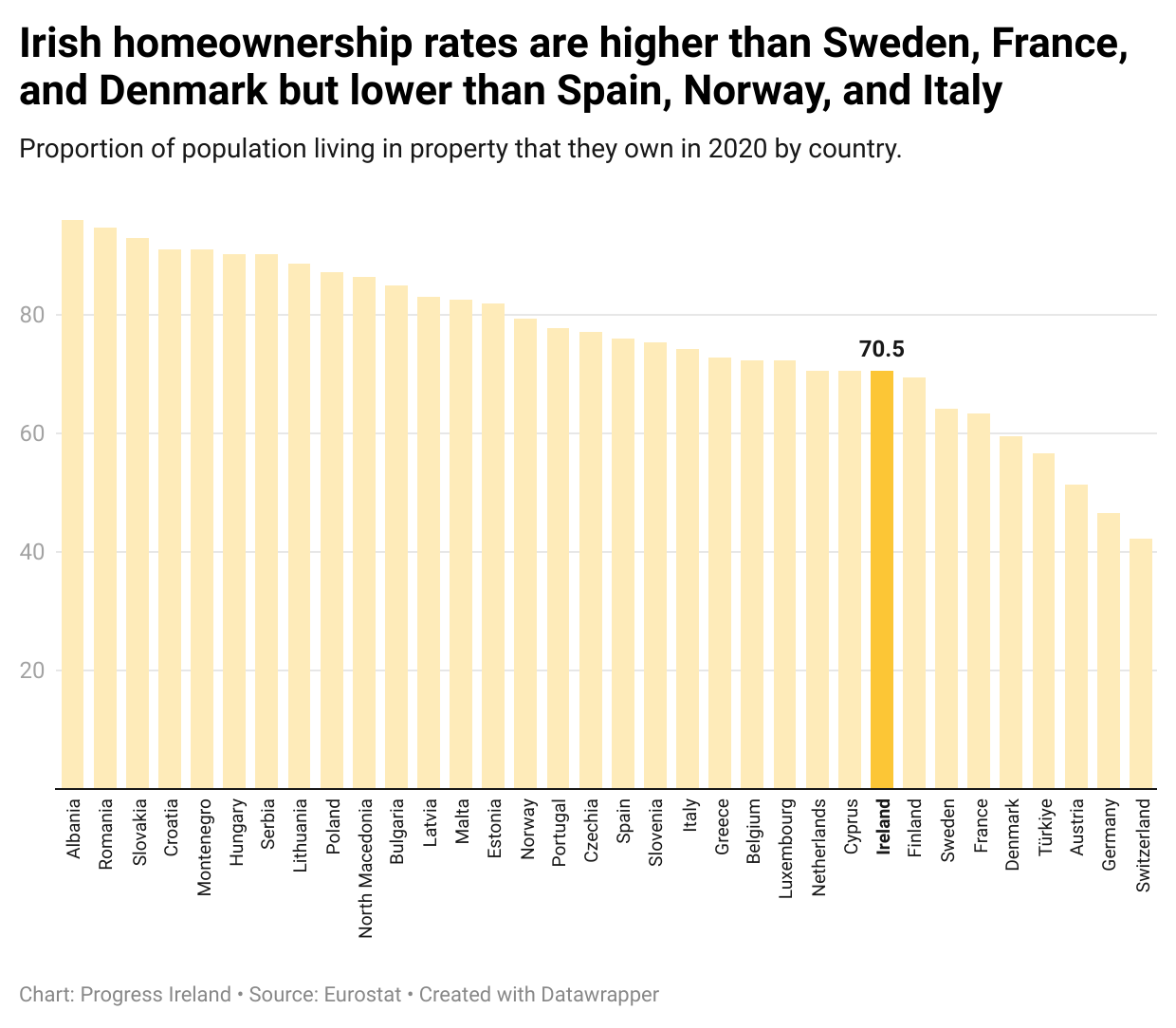

The second thing to note is that Ireland’s homeownership rates are above the Western European average of 61.2 per cent. Between 2005 and 2022, Ireland averaged 72 per cent owner-occupation. This graph shows the 2020 homeownership rates across Europe.

Irish homeownership levels do not seem like a cause for concern. But some commentators are concerned about that changing. The new homes being built, they suggest, are not being built for households but rather for investors. But is this true?

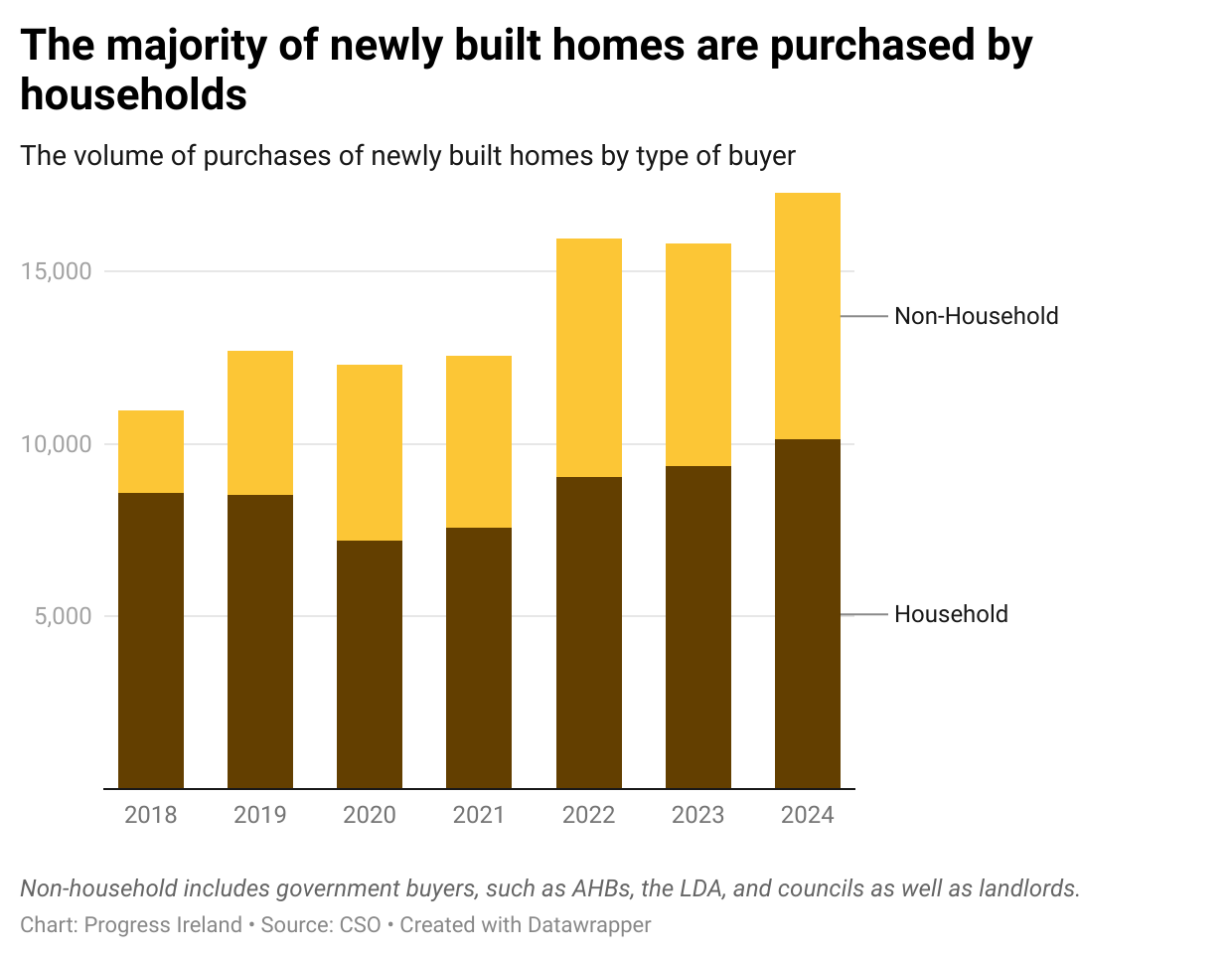

Not quite. The majority of new homes are being purchased by households as shown here.

The purchases that fall into the ‘non-household’ category include those bought by AHBs, the LDA, local authorities, and landlords. But I am not aware of any evidence that the majority are being bought by private landlords. Looking across all purchases due to non-households (both new and existing), the largest group is defined as O/P/Q by the CSO. That category includes all state agencies, departments, and some AHBs. It also includes some private actors in the areas of education and health. By 2024, O/P/Q was the single largest non-household purchaser of homes.

When we zoom into the cities, the case for worry becomes stronger. Maybe it isn’t that Ireland is going to become a nation of renters but that Irish cities will be made up mostly of renters. The worry is based on the following fact. The majority of new homes in Dublin are apartments. Of these, the majority are being bought by either the council, AHBs, the LDA or private investors.

In Q4 of 2024, Dublin city saw 1,157 new homes. Of these, 1,115 were apartments, 20 were ‘scheme’ houses, and 22 were single houses. In previous years the relative numbers were comparable too.

The majority of new apartments are not owner-occupied. In 2024, only 111 apartments in Dublin city were sold to household buyers. The rest were bought by AHBs, the LDA, and investors.

The worry can be summed up as follows: The majority of new builds in Dublin are apartments and the majority of apartments are for rent whether the landlord is from AHBs, the council, the LDA, or the private rental market. If you’re in a newbuild in a city in Ireland, you’re probably in an apartment. And if you’re in a new apartment, you’re probably renting it. To complete the thought: if we carry on building apartments for rent, Dublin and the other cities will be majority renting. And that, by our earlier thought, may be bad.

There are three points I want to make about this worry. The first is about urban mortgage rates. The second is about the implicit diagnosis of why we are building so few to-buy apartments contained in the worry. Third, its proponents massively underestimate the demand for rental accommodation in Irish cities.

First, urban mortgages are at parity with non-urban mortgage types. While the proportion of Irish mortgages in urban areas has fallen since the Celtic Tiger years, they are still relatively strong. In fact, urban, suburban and town, and rural mortgages each make up a third of mortgages in Ireland.

Second, Progress Ireland has written about the first question of why apartments are so expensive here, here, here, and here. The primary reason why there are so few household purchases of apartments is that they cost too much to build. The government has introduced measures, such as reducing the regulatory and tax burden on development, which may see costs come down. But more will have to be done if we are to see families purchasing their homes in Irish cities. Here, I share the worry that too few families are buying in the city. However, the culprit is not the over proliferation of rentals. Rather, as I argued here, it is the lack of available land capacity, high regulatory barriers, and planning restrictions.

Are there too many homes to rent in Irish cities?

Third, the worry that Ireland is becoming a nation of renters implies strongly that there are too many rental homes being built. One commentator, Lorcan Sirr, has made this point repeatedly.

But it is hard to square that with how few rental homes are being listed on DAFT. On the day of writing, there are 16 one bedroom homes available to rent (including studios) in Cork city and suburbs. In Waterford, there are just five one bedrooms listed for rent. In Galway, there are just six. But is this enough?

(An aside: I don’t know what fraction of rental homes listed in Ireland are listed on Daft. There is also the issue of the same property being listed on different websites. However, Daft is so comprehensive that it’s widely used by policymakers. A defensible guess is that, if a one-bedroom apartment is listed publicly in Ireland, there is a 75% chance it will be listed on Daft.)

Ronan Lyons has written about Ireland’s missing rental homes here. He estimates that, as of 2023, Ireland is missing approximately 200,000 rental homes.

To calculate this, Lyons takes the flow of new advertised rental units. In 2023, there were about 30,000 rental homes advertised on DAFT. When there were about 100,000 rental units advertised, rents fell. So, a simple back of the envelope calculation would suggest a missing 70,000 rental units.

Since the typical tenancy is around three years, the shortfall stands at about 200,000. This is because to get the shortfall of listings for a given year, we have to take into account the turnover of homes. We do that by multiplying the shortfall by the number of years in a typical tenancy.

Anyone who has rented in Ireland will not be surprised to hear it: Ireland is far from a nation of renters. At the moment, it is a nation where it is difficult to find somewhere to buy or rent. As regular readers will know well: Ireland needs more homes of every kind and tenure type (including private rental homes).