The transition to a new electricity system is not simple or easy. We are moving away from Moneypoint’s giant coal yard and towards a system of hundreds of small wind farms. The new system is more fragile than the one it’s replacing.

There can be no doubt the dirty old energy system needed replacing. To reduce carbon emissions, a system of taxes and subsidies and carbon budgets and legal targets has been established. The electricity system hasn’t been decarbonised yet, but governments are taking the problem seriously. Progress has been made.

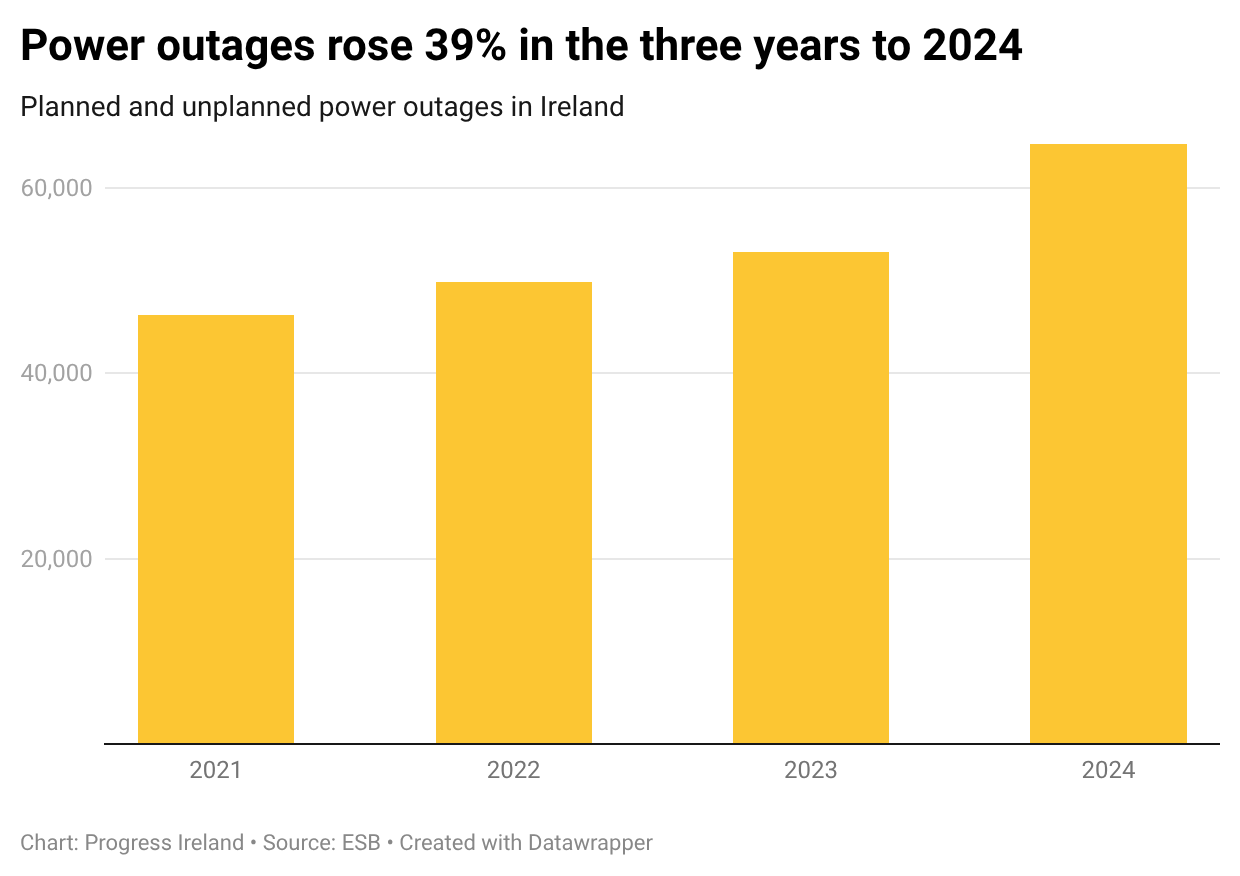

While we’ve made progress in thinking through the decarbonisation problem, I’m not sure we’ve cracked it yet. I worry we’ve taken the reliability of the electricity system for granted. And I worry a failure to guarantee reliable energy could sink the whole project.

Trilemma

An energy system needs to do three things at once. This is what is known as the energy trilemma.

The first is that the energy system must supply the right quantity of energy at a reasonable price. It must be affordable.

The second is that the system must be reliable. Energy is an input into everything. Without energy, modern life doesn’t work. The system must have everything it needs to generate energy, and the energy must not stop flowing.

The third is that the generation of energy must not pollute the climate. So it must be sustainable.

The environmental movement has won the argument that, in addition to being affordable and reliable, the energy system must be green. Carbon taxes, tradable permits and subsidies to green energy help integrate the requirement for green energy into the system.

Less successful has been the integration of the need for green energy with the need for reliable energy. The need for a secure and reliable energy supply sits awkwardly with the need for decarbonisation. The requirement for green energy and the requirement for secure energy are in conflict because the sources of green energy are intermittent. In other words, green sources of energy can’t be relied upon 100 per cent of the time.

Intermittency hasn’t been a big deal over the last 20 years, when green energy has been a relatively small share of the overall system. But as green energy’s share has grown (about 40 per cent of electricity generated in Ireland), guaranteeing reliability has gotten trickier.

This is not just a problem for reliability-preferrers. If the energy system we’re trying to build can’t reconcile the need for reliability and decarbonisation, it is decarbonisation that will end up being jettisoned. People want green energy. But they don’t want it at the expense of a functioning energy system and economy.

Intermittency

Being grey and gusty, Ireland’s clean power source of choice is wind energy.

The challenge with wind is its intermittency. With wind in Ireland, the intermittency problem is less about windless afternoons than the windless week that comes along once every year or two.

Windless weeks are a big problem because we don’t have the technology to store a week’s worth of energy. Lithium-ion batteries are improving all the time. But they’re useful for balancing out energy demand and supply within a day. They can’t store a week’s worth.

Other mitigation strategies help at small scales but don’t get you to a week of energy. Interconnectors, for example, are often proposed as a solution. However, wind is correlated across north-western Europe. When the wind is not blowing in Ireland, it is often not blowing in Britain either. And we can’t all rely on French nuclear power.

Or take solar power. Ireland is cursed with a northerly latitude. Solar radiation in Ireland is 85 per cent lower in winter than summer. So we can’t rely on solar to mitigate energy shortages on windless winter days.

Hydrogen is frequently proposed as a long-duration storage solution. The idea is to use surplus renewable electricity to split water into hydrogen and oxygen, store the hydrogen, and later convert it back into electricity. In theory, electricity could be generated using wind, converted into hydrogen, stored in large underground salt caverns, and then reconverted into electricity when needed.

A great deal of hope is being pinned on hydrogen. The Irish government’s National Hydrogen Strategy states that renewable hydrogen will play an important role in addressing system stability and seasonal wind variability. EirGrid has described hydrogen as potentially “critical” to future energy security.

However, not all expert bodies share this optimism. The Irish Academy of Engineering argued that producing green hydrogen via electrolysis, transporting it, storing it, and then burning it to generate electricity is inherently inefficient. According to the Academy, around 80 per cent of the original electricity input is lost, due to physical constraints rather than avoidable waste.

None of this implies that hydrogen has no role in the energy transition. It may prove valuable in industry, shipping, or as a niche long-duration storage option. But it’s not a carrier of energy for the windless week I mentioned earlier.

A system dominated by wind power will be sustainable. But it will not, without further investment, be reliable. To build a system that’s both sustainable and reliable, we need more stuff: storage, transmission, interconnectors, dispatchable backup generation such as gas peaker plants, or demand-side management.

When the cost of all this stuff is omitted, prices give a misleading picture of both the cost and resilience of the electricity system.

Internalise the externality

All of which is to say that the true cost of electricity is not just the €/MWh required to generate it.

Electricity that requires additional investment in storage, backup generation, or demand management to meet reliability standards is not equivalent to electricity that does not.

Sir Dieter Helm, an economist at Oxford University, has proposed a reform that would address this problem. He calls it Equivalent Firm Power (EFP).

EFP is a way of comparing all sources of power like-for-like. EFP asks: if we remove this resource, how much perfectly reliable capacity would we need to add back to keep reliability the same? Under EFP, providers would be paid for their ability to provide firm power. They could bundle whatever generation and demand-side technologies they saw fit to maximise EFP.

In this way, EFP works like a carbon tax. Both carbon taxes and EFP ensure that the price that’s paid incorporates all the costs that are involved in providing the electricity.

Here are four reasons to price energy capacity this way.

The first is that it aligns energy producers incentives with what the country needs. Projects earn more when they can deliver in windless weeks. So developers optimise accordingly.

The second is that it is technology agnostic. Any bundle of new or existing technologies might prove to be the lowest cost one. EFP allows for variety and experimentation. And it doesn’t require the regulator or government to make big bets on specific technologies.

The third is that it pulls forward technologies that address reliability: demand-side management, batteries, turbines, nuclear, interconnectors, whatever else. EFP guarantees demands for those technologies and justifies investments in them.

The fourth is that it places system costs on those that are responsible for them. Under the status quo, the group that pays for systems costs is different from the group that builds renewables. This misalignment results in the under provision of systems infrastructure and technology.

The thing to remember is that we’re already paying these system costs. We’re just doing so in a clumsy way. EFP would reduce wasteful system costs. And the system would be more reliable.

To be sure, Ireland has capacity remuneration mechanism (CRM) auctions. But EFP prices firmness, while the Irish CRM prices energy availability at peak. That subtle difference changes incentives. CRM tolerates intermittency and fixes problems downstream. EFP forces intermittency to be solved at source.

Ireland has made progress in decarbonisation by attacking the problem at the source. Carbon taxes shifted incentives and pulled forward investments in sustainable power. The same thinking will make our renewable-based system reliable.