In her red stetson hat, Sonja Trauss was cock of the walk at the Progress Conference in Berkeley last month. The conference was a gathering of policy nerds, technologists and YIMBYs; Trauss has a good claim to be the original YIMBY. She was in good form because, two weeks before the conference, California YIMBYs had scored their biggest win ever.

A new law called SB 79 allows the construction of apartment buildings near California’s bus and train stops, by right. The bill is the culmination of 11 years of campaigning. It legalised the construction of up to 1.5 million extra homes.

Trauss co-founded Yes In My Back Yard, the San Francisco Bay Area Renters’ Federation and the California Renters Legal Advocacy Fund. She is the main protagonist of Conor Dougherty’s book Golden Gates, which tells the story of the crusade for affordable housing in the US.

The YIMBY movement wants more housing built near jobs. It wants more apartments in quiet suburbs. In three quarters of California’s developable residential land, it’s illegal to build anything other than a single home with a garden.

To get this done, YIMBYs have put in patient years attending community meetings, gathering supporters and lobbying legislators. They have specific rules they want changed. It’s also clear who their opponents are: the NIMBYs who don’t want apartment buildings on their residential streets. The NIMBYs have their own organising and lobbying efforts. They have rules they don’t want changed. It’s a fair fight.

In California and the rest of the US, the bottleneck to getting housing built is political in nature. It’s about laws and lawmakers. Changing the laws requires a big coalition, lots of meetings, campaigns for office, and the lobbying of politicians. A public hearing, for example, over whether to allow slightly taller buildings in San Francisco ran for 10 hours, and was finally defeated 4-3.

Trauss and I swapped notes on the politics of housing in Ireland and the US. She gave me this sticker, which lives on my notebook:

I explained to Trauss that in Ireland, this isn’t how things work: you can’t legalise housing. You can’t legalise tall apartments beside train stations, for example, because they’re not illegal. There is no rule banning tall apartment buildings beside train stations.

But, as we know, in Ireland, there are almost no tall apartment buildings beside train stations. That’s because it’s illegal to build without planning permission, and the planning system very rarely allows them1.

At this point, Trauss looked confused: “So In Ireland, apartments are neither allowed or banned?”

“That’s correct.”

The Irish system

Here is a quick sketch of how Ireland regulates the use of land.

In Ireland, a project must apply for planning permission. The Office of the Planning Regulator has a useful guide to the process. It says: “All planning applications are assessed against the policies, objectives and standards contained in the Development Plan before a decision is made to grant or refuse planning permission.” Development plans are set at the local authority level. They in turn must comply with regional and national plans.

The Development Plan is the planning rulebook. Planners judge applications against it. What’s in it?

The first thing to say is, it’s hard to even find the 2022-2028 Dublin City Development Plan. Despite being an electronic document, the council has chosen to split it into 24 separate PDFs. Added together, these 24 PDFs sum to 2,447 pages.

Note: I’m leaning on ChatGPT, Gemini and Claude a lot for this piece because no sane person could be expected to manually pore over two thousand pages of planning documents. If there are errors, blame the voluminous PDFs – not the LLMs. Nor me.

The issue with these Development Plans is that they both are, and are not, rulebooks. They’re rulebooks in the sense that they guide planning decisions. But they’re not rulebooks in that their word is not final. The things they’re full of are not rules.

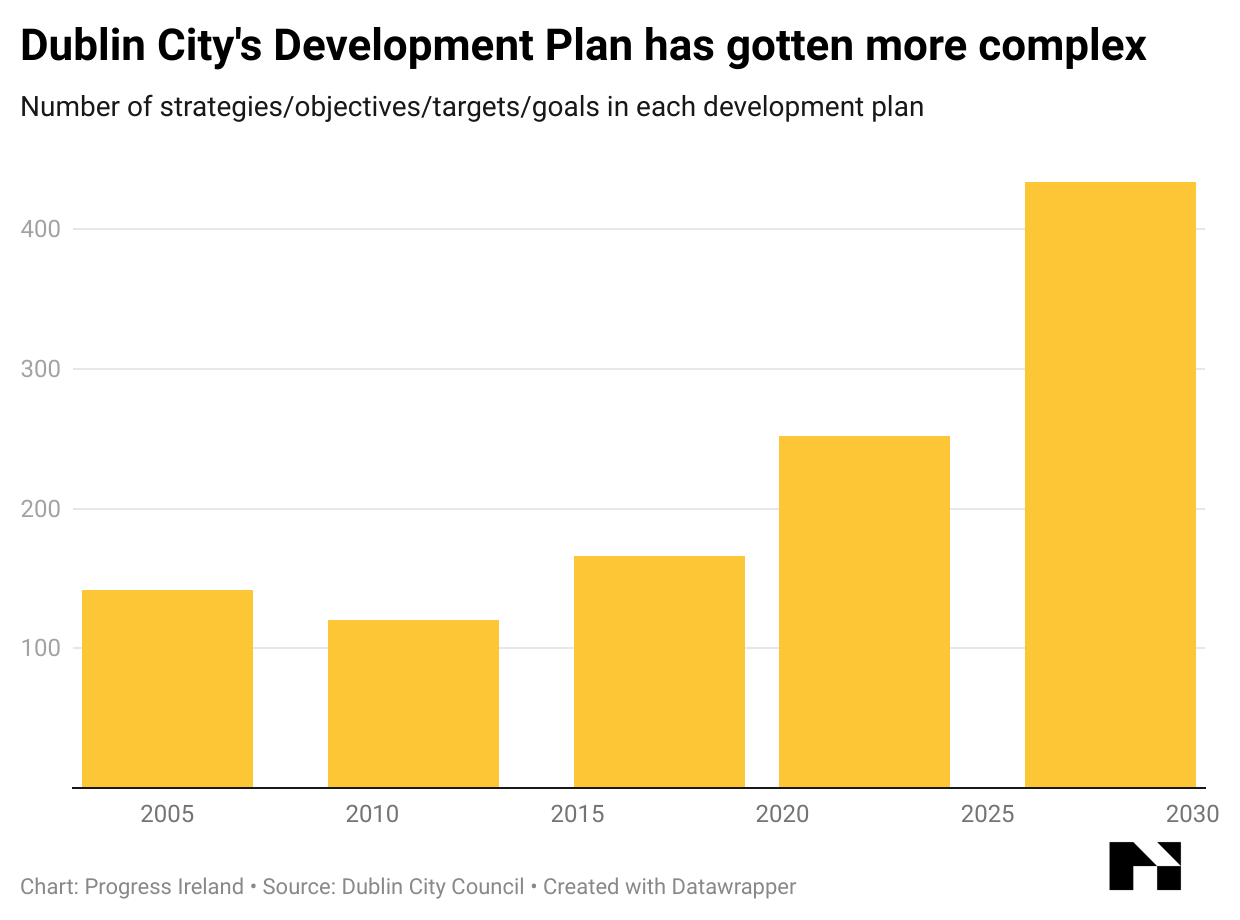

In place of specific rules, Development Plans have targets, goals, strategies, policies, and objectives. The total number of targets/goals/strategies/policies/objectives is very large: there are 434 in Dublin City’s most recent development plan, per ChatGPT.

No one target/goal/strategy/policy/objective is sacrosanct. The planning officer’s difficult job is to balance these — let’s call them objectives — to come up with the fairest answer possible, and grant or deny planning permission on that basis.

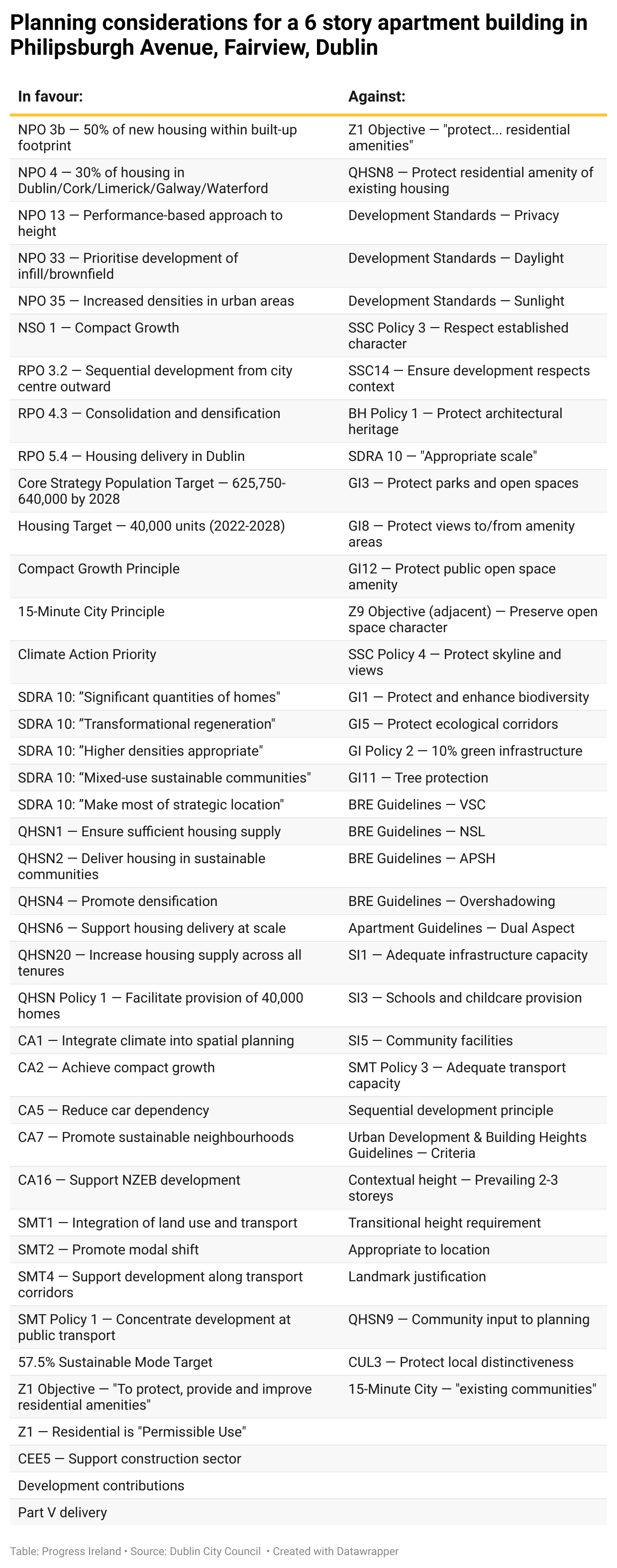

The 434 objectives in the Development include every objective for every neighbourhood and type of land use. If you limit the analysis to an application for one project – say, a six story apartment building on Philipsburgh Avenue in Fairview – you’re left with 40-60 relevant development plan objectives.

The following table sets out the objectives that are relevant to a planning application in Fairview. The left column shows the objectives that would favour granting permission; the right hand column shows the objectives that would oppose it.

The first thing to note is how long it is. It has 40 relevant development plan objectives that lean towards granting permission and 36 objectives the count against it.

The second thing to note is how many of these objectives directly contradict each other. Housing targets, compact growth objectives, climate objectives, and transport objectives support building mid-size apartment blocks on transport corridors near the middle of the city. But planners are also obliged to limit density because higher density doesn’t match the existing low density context, because high density casts shadows, because it’s hard to achieve high density while maintaining a 22 metre cordon around the building, and because adding homes might fail to protect residential amenities.

How it’s possible to increase city-wide density while matching its existing low-density context, and without casting shadows, I do not understand.

Another point to note is that the Development Plans have gotten more voluminous and confusing over time. I asked Claude to count the number of objectives/policies/strategies/goals in the last five development plans.

Local authorities aren’t necessarily to blame for this increase in complexity. Dublin City’s former head of planning John O’Hara said: “The growth in the number of bodies who want to load their views onto a development plan is amazing. EU, UN, disabled access, every sector thinks they can load their responsibilities onto the development plan. And if you leave anything out, you’re the world’s worst. This should be a user-legible plan. The sin of omission in a development plan is the biggest sin of all.”

This is not the only way to organise planning. Almost every other developed country (with the exception of the UK) regulates planning with a straightforward rule book. The rules say what can and can’t be built. If a project conforms to the rules, it can be built. If I wanted to build a six story apartment building in suburban Paris, I would check whether the project complies with eight specific rules regarding setbacks, height, floor to area ratios, parking and so on. I could collect my certificate from the council. I would comply with other rules around access etc. And would I post the notice on the wall. Two months later I’d be good to go.

“That’s not how the system works”

I was moved to write about all this by an exchange I had with UCD’s Orla Hegarty on The Irish Times’ Inside Politics podcast two weeks ago.

I wanted to make the point that, in Ireland, land use rules are not written by elected representatives, as they are in California. I said that the rules are, for the most part, written by local authority planners. That’s an issue because planners are unaccountable. It’s not possible for an Irish Sonja Trauss to start, and win, an argument in favour of more building. It’s not possible because there’s nobody to argue with. There’s no door to knock on.

I said on the podcast that planning “is not a political issue. It’s controlled by technocratic planners.” Orla Hegarty took issue with my characterisation. “That’s not how the system works,” she said. “It’s democratically debated and adopted with technical advice from the officials”.

“The framework for the decision making has been approved democratically by the Council in a process that takes a number of years and gets into a huge amount of technical detail,” she added.

I submit, if it were the case councillors rather than planners control planning rules, we would see more political arguments about planning. Politicians in Ireland are happy to argue about everything else. And in other countries, the political fights about planning are intense. But we simply don’t see them here. The argument over seomraí earlier this year was the only time I recall a planning question breaking through to mainstream debate.

When I asked Dublin City councillors on the planning committee where local development plans come from, they told me officials write them. The documents are 3,800 pages long — of course the councillors don’t write them. One councillor, Patricia Roe of the Social Democrats, told me how some officials operated: “This was a stunt [council officials] pulled — they changed the zoning on a number of maps. They changed it without saying anything. And this was noticed by councillors at the last minute. And that’s how that was rushed through on the night.”

Former senior planner John O’Hara doesn’t disagree with my characterisation that councillors control the process: “[The councillors] are right to trust [the professional officials],” he told me.

Deus Ex Machina

Our planning system is the biggest single determinant of price, quantity and quality of housing. If it’s not working well, what are we meant to do about it? If it’s not working well, and we can’t adjust it, is that not a serious problem?2

What would it take for an Irish Sonja Trauss to campaign for an Irish SB 79, the California bill that legalised apartments near bus and train stops?

There is an unorthodox way to do it within the Irish system. A national planning statement could be issued by the Minister for housing. It could say, as in California, that apartments of a certain size are permitted within a certain distance of existing bus and rail stops. The statement would reach “over the top” of local authorities, such that their local development plans would need to comply with it. National planning statements are a brand new power, created by the 2024 Planning Act. They have yet to be used.

I would be happy if a national planning statement, like a deus ex machina, descended from the Housing Minister’s office and resolved the housing shortage. But even if it did, it wouldn’t fix the fundamental problem. It’s not right for our housing system to be controlled by an unaccountable bureaucracy. And the results are not good enough.

To be sure, giving more control over land use to elected representatives is not guaranteed to resolved housing scarcity. It could lead to a NIMBY takeover. But in my view the debate is the first step.