Last week, the government issued the third housing plan in nine years. In July, Progress Ireland published our own housing plan. Our plan wasn’t intended to be comprehensive. But it was intended to address some major issues on the supply side. Our plan was both diagnostic and constructive. It sought to point out the biggest bottlenecks and suggest solutions for addressing them.

Our plan was organised under three headings: cutting costs, freeing up land, and speeding up planning. So how does the government’s new plan compare to ours under these headings?

Cutting costs

First up is costs. It is worth saying why cutting costs should be central to any housing plan.

On the affordability side, you can think of high costs like a floor on prices (of new builds). If it costs €400,000 to build a house, that house will have to sell for more than that. Half of Irish households earn less than €60,000 a year which puts their maximum mortgage in the region of €240,000. In the cheapest region to build, the North West, it costs about €360,000 to deliver a new three bed house. Simply put: the cost of delivering a standard three bedroom home is higher than the majority of Irish households can afford.

This is why it is important to know what the break-even cost of the minimum standard home is, be it an apartment or house. By minimum standard home I mean the minimally compliant home with regulation. If that home costs more to deliver then most people can afford, then something has gone wrong. I don’t think it is an overstatement to say that once the cost of a minimum standard home is higher than people can afford, it is illegal to build affordable homes without subsidy.

The same reasoning applies to rentals. Ronan Lyons calculated the minimum break-even rent of a newbuild apartment in 2017. Not taking into account site costs, the break-even rent of a two bedroom apartment in Dublin’s city centre is about €1,700. Taking into account site costs, that figure rises to about €2,000-2,200 a month. If we define an “affordable rent”, as many do, as spending no more than a third of income on rent, a couple would need to earn over €100,000 per year to “affordably” meet the break-even costs.

The big problem with this is twofold. First, it means that the homes that get built aren’t affordable to most households without state support. Second, it means that fewer homes will be built. This second point is important. If costs outpace a household’s ability to pay, then there will be no incentive to build. Low levels of supply coupled with growing demand will, in turn, drive up prices even further.

Such a system will deliver few and expensive homes. The system will also be propped up by growing state spending. All of which has materialised: output has fallen, construction costs, prices, and rents are up, and state spending on housing is at an all time high.

All of this is to say, getting costs down should be at the heart of any plan to fix the housing shortage. The gap between what people can afford and breakeven costs has to be closed. Thankfully, the government’s plan attempts to close the gap.

The gap can be closed in two ways. Either, the purchasing power of households can be increased or costs can come down. In Housing for All, the government focussed on the first option. This is why the former Minister O’Brien was somewhat correct when he said that schemes such as Help to Buy and the First Home Scheme are “supply side” measures. The thinking was that so long as households can afford to cover development costs plus profit, then the industry will be incentivised to build.

The new plan takes the other option: it seeks to get costs down. It does three things to address costs (or, to be more accurate, the new plan summarises three things that have already been done to address costs). Though the subsidies to first time buyers will continue.

First, the government has introduced new apartment standards. The aim of the new guidelines is to get costs down by pulling back on some regulations. This is something we have argued for here, here, here, and here. While high standards mandate good things- a big south-facing flat with a balcony is better than a smaller, north-facing flat with no balcony- they also drive up costs beyond what most people can afford. There is a trade-off between increasing regulation and costs. And it is to this government’s credit that they have decided that nice homes that people can afford are better than even nicer homes that very few can access.

Second, the government has introduced two tax breaks in the budget. First, they will reduce the VAT on sales on new apartments to 9 per cent (down from 13.5 per cent). Second, they have introduced an enhanced corporation tax deduction. Before, when paying corporation tax, a developer would deduct their costs from their revenue and pay out corporation tax on the profit. Put another way, in calculating their profit, developer’s could deduct 100 per cent of costs. The enhanced deduction will see developer’s deducting 125 per cent of costs (up to a limit of €50,000 per apartment). This will reduce the overall tax liability for development. (In addition, cost rental developments will be entirely exempt from corporate tax).

Third, schemes like Croí Cónaithe will continue. This scheme provides a grant of up to €120,000 to enable developers to sell to enable owner-occupiers without going below break-even costs.

As a bonus, there are some reasons to think that speeding up planning and increasing land supply will, together, put downward pressure on costs. For example, soft costs, such as finance costs, increase when planning risk is high. When land supply is low, land costs go up. Together with the three policies to cut costs, the hope is that breakeven costs come down.

There are further steps that can be taken. Such as pattern books for more affordable typologies. Pattern books are pre-approved “off the shelf” detailed designs for homes that can be used by builders. Mid-rise apartments, in general, are much cheaper to deliver than high-rise ones, without sacrificing high density. The government has taken some steps to encourage these typologies, but it can go further. Using a National Planning Statement to, in effect, ‘pre-approve’ specific designs of lower cost homes would reduce planning risk, encourage cheaper construction, and hopefully utilise some of Ireland’s SME builders. As discussed on this newsletter before, Canada and New South Wales have taken this approach recently.

More land.

In our July plan, we made the case that more land was an important ingredient of housing reform.

Freeing up land is important because a healthy supply of zoned and serviced land drives down land costs, accelerates housing supply, and may increase construction productivity. The converse is also true: artificially constrained land supply drives up costs, slows down supply, and may decrease construction productivity.

The good news in the new plan came three months ago with the introduction of Housing Growth Requirements. The requirements, which were introduced via section 28 of the old Planning Act, encourage councils to zone (collectively) for up to 83,000 homes per annum.

These requirements are not quite mandatory. Councils must zone for about 55,000 homes but may zone for up to 50 per cent beyond that. One problem with a requirement to zone more than this is that the National Planning Framework, which set the original targets, underwent various procedures, such as a Strategic Environmental Assessment. With the apartment guidelines being challenged in the courts for allegedly not going through the right procedure, the government is probably right to be cautious.

To be sure, zoning alone won’t solve the problem. Zoned land must be serviced to deliver homes. It is positive that the government’s plan includes substantial increases to infrastructure spending.

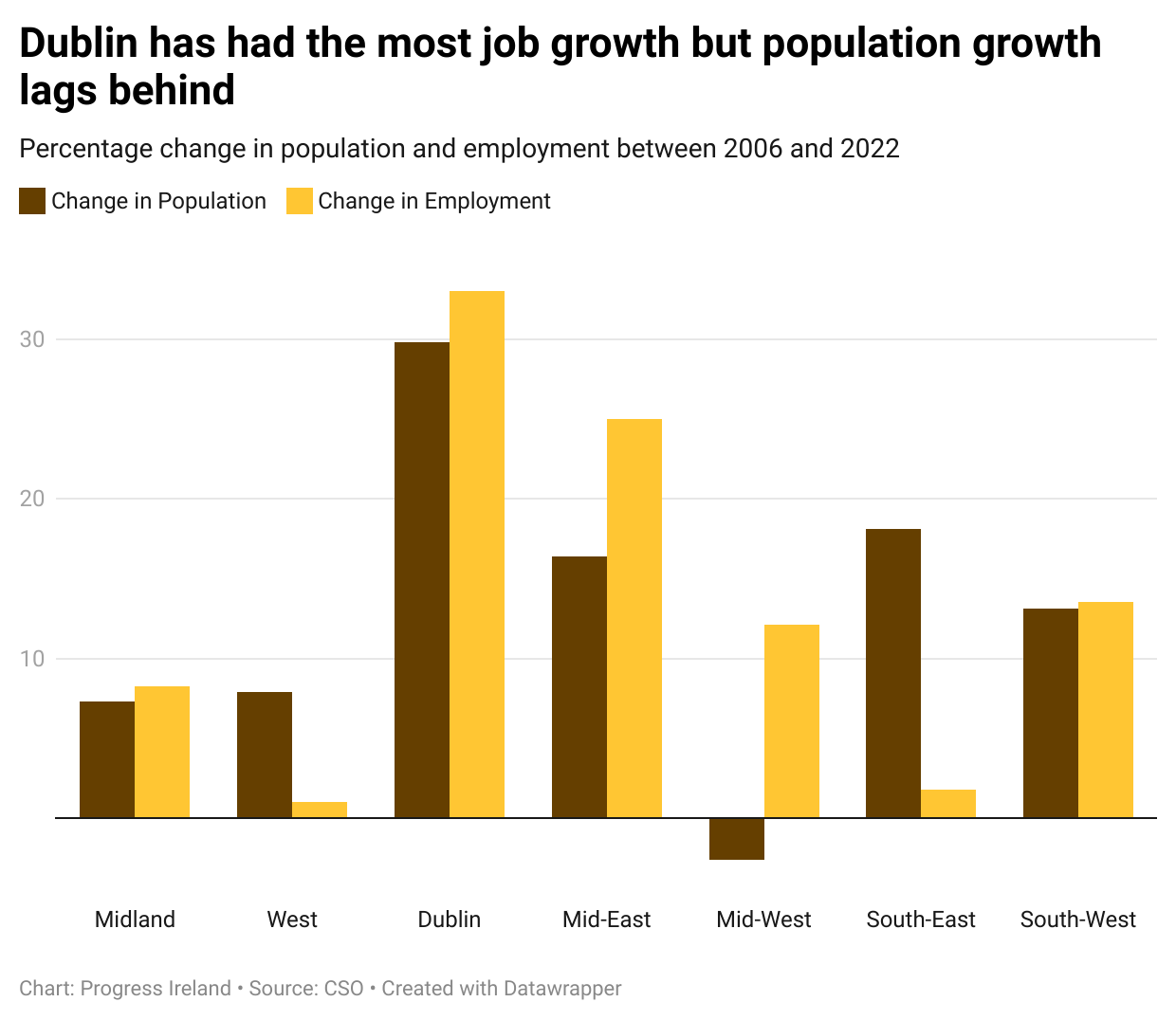

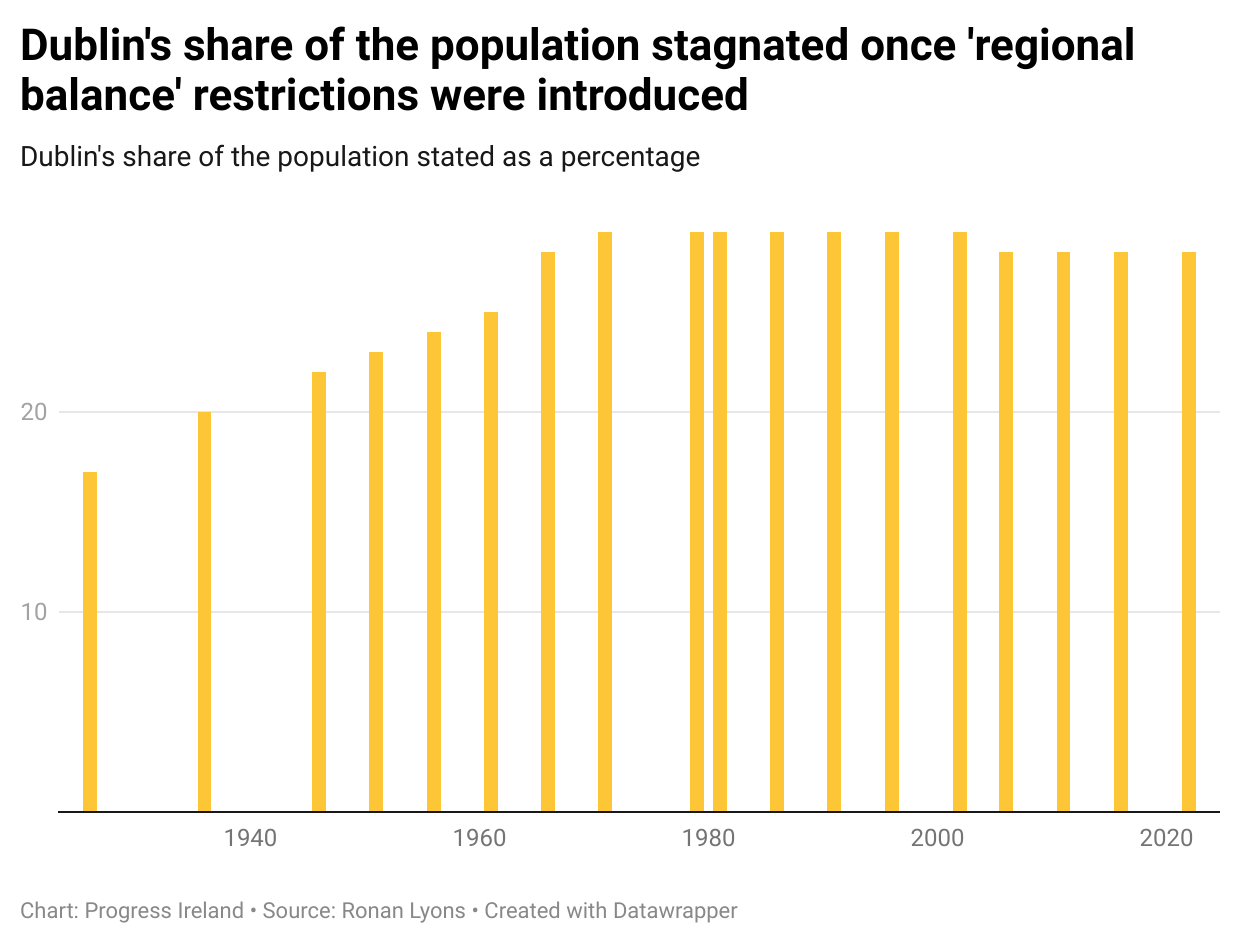

However, location matters. While Dublin is home to high job growth and high prices, land supply remains proportionally restricted in the capital.

Dublin’s proportion of the State’s population stagnated soon after the original planning act was brought in. The capital, rather than being a net importer of people, has been a net exporter for about 20 years. Some may regard this as a victory for regional balance. But job growth has continued in Dublin due to agglomeration effects. The result has been a capital where many people have to work but can’t afford to live.

But there is some hope for Ireland’s cities (including Dublin) in the new plan. And that brings us to the third heading: planning.

Speeding up planning

Progress Ireland has been arguing for a clearer, more predictable, and consequently, a faster planning system since we launched. Clarity about what gets built and where reduces risk and, ultimately, gets more homes built.

We are happy to see the plan reiterate the importance of planning exemptions. Planning exemptions create a rules-based system that allows small development to continue without having to undergo a planning process. Exemptions included in the plan are seomraí, internal subdivisions, and the conversion of older buildings into new homes.

The most important part of the government’s plan on planning is under the heading of “new urban communities.” This heading refers to Urban Development Zones or UDZs. These are areas, designated by the state, which are to be masterplanned. A masterplan is a detailed plan for an area which contrasts with development plans which are typically policy based. Where development plans set out vague objectives, relating to climate, architecture, public realm, housing, and so on, masterplans spell out precisely what can be built and where. There are lots of benefits to masterplans but speed is definitely one, as shown in this recent paper by Ronan Lyons and Eamon Sweeney.

UDZs present a massive opportunity for large scale housing delivery. They are designed to create nice neighbourhoods. But one issue that will arise is fragmented ownership. It will be difficult to deliver large scale new urban areas by negotiating individually with landowners. CPOs will be used, in some cases, but as a rule these are controversial, slow, and a last resort measure. The new plan recognises the problem of fragmented ownership, it said

CPOs can help to mitigate issues related to fragmented ownership, which can hinder large-scale development projects. In this way, the State can consolidate strategic land banks and can provide a clear pathway for developments to proceed. By ensuring fair compensation and engaging with affected stakeholders, authorities can foster a more cooperative approach to land assembly.

To help build these new urban areas, the government could supplement the UDZs process (which is already enacted law, as part of the Planning and Development Act 2024) with a land readjustment process.

Land readjustment tries to solve problems downstream of fragmented ownership. Say a planning authority is trying to masterplan an area and deliver infrastructure alongside new homes. One major problem the plan faces is that there are lots of land owners with plots split in inconvenient ways.

At present, our policy tools include asking nicely or compulsory purchase orders (CPOs). Neither works well. CPO is acrimonious, slow, risky, and costly.

What land readjustment does is provide a mechanism for landowners to benefit from the new development in a way that incentivises them to say yes to it.

The basic idea goes like this. Landowners can ‘pool’ their plots together for the new development under a masterplan. Once pooled, a developing authority (whoever it ends up being: the LDA, local authority, a special purpose vehicle) replots the land to suit the plan and dolls out repackaged plots that are, because of the plan, of greater value than the original plots.

The reason why this helps is because it provides an incentive to pool land. Where before policy provided just a stick, with land readjustment, it can provide a carrot too. Similar policies have been successful in Germany and Japan. Given the urgency of delivering UDZs at pace, the government could consider including land readjustment in their suite of tools to activate land quickly.

A big part of solving the housing shortage is understanding the main obstacles. The government’s plan isn’t perfect. But it addresses the key barriers of high costs, constrained land supply, and slow planning.