Everyone wants to solve the housing crisis but what does “solving it” look like? Is it “solved” when everyone, everywhere, has the place they want, where they want, at the price they want? Or is it “solved” at some point before that?

Tolstoy opens Anna Karenina with the famous line “happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” Is this true for housing systems? Are happy housing systems alike and unhappy ones different?

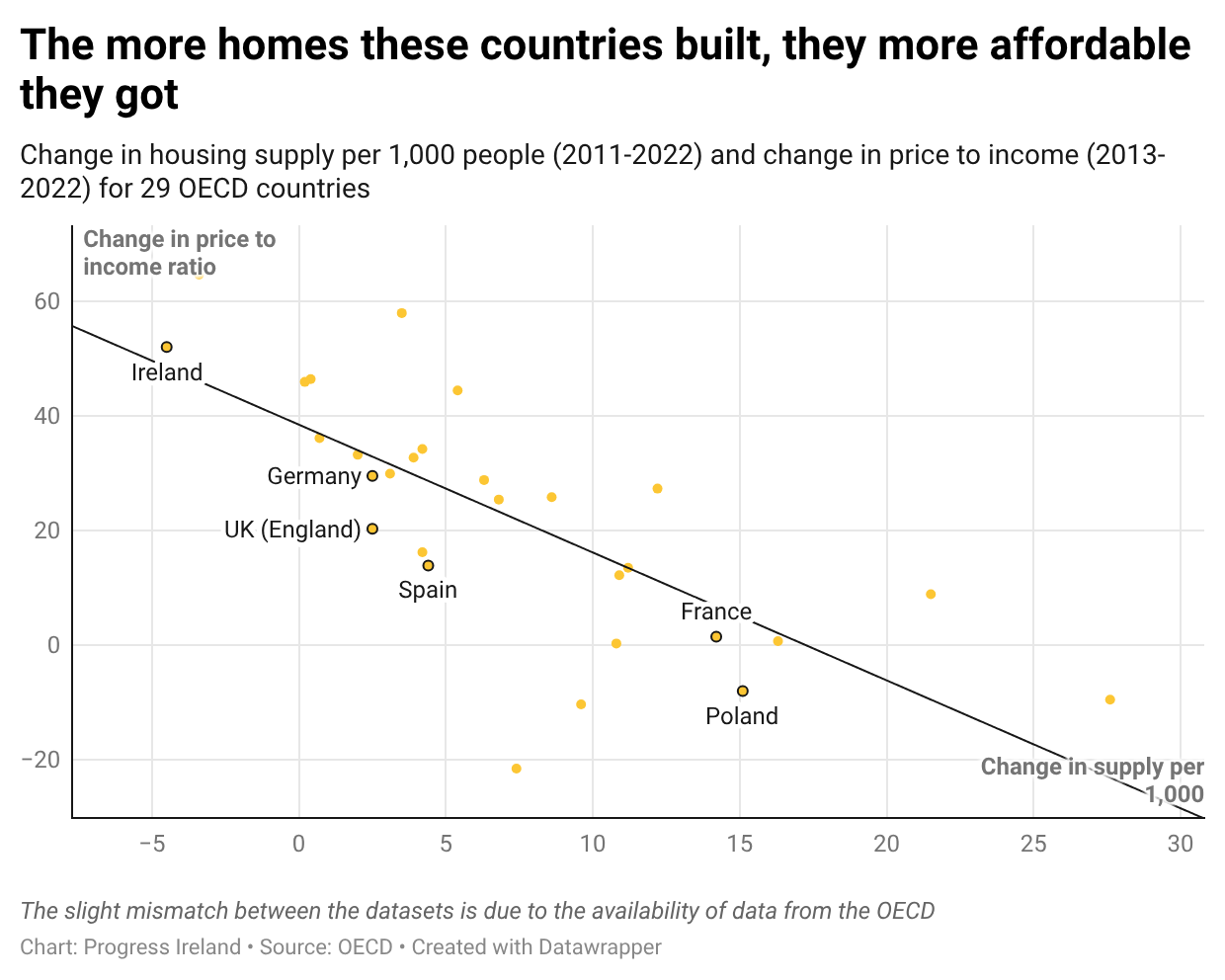

What makes a good housing system? Good housing systems offer affordability in different ways, they offer different types of homes, they offer accessibility in different ways, and their quality comes in different forms. But they all share one thing: abundance.

Affordability

The first thing people look for in a good housing system is affordability. Your house shouldn’t eat up too much of your income. What’s “too much”? The generally accepted threshold for affordability is 30 per cent after tax income.

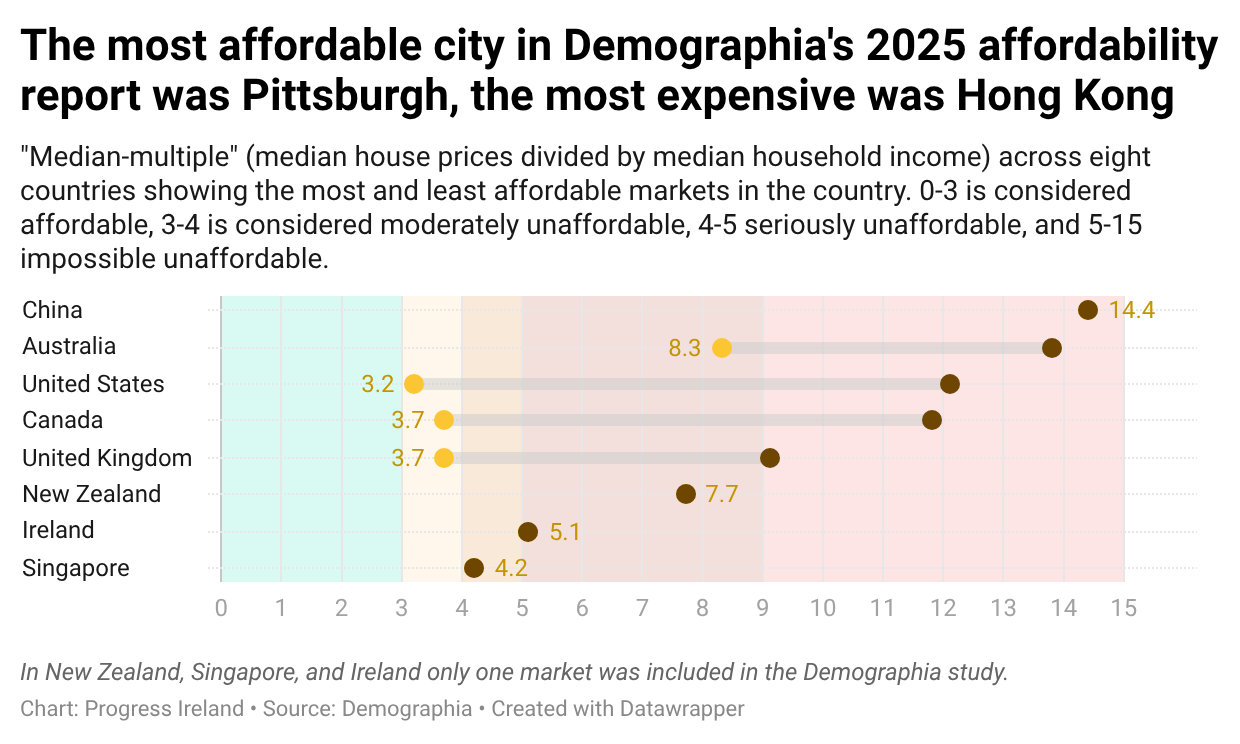

Another good measure of whether a housing system is affordable is the ratio of the median household income to the median house price. Each year, the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University publishes a housing affordability report. The report measures an estimate of the “median-multiple” of cities. Their report shows Dublin’s median-multiple is 5.1 which they put in the “severely unaffordable” category. Pittsburgh, PA was the best performing city in the report, with a median-multiple of 3.2. The least affordable city in the report was Hong Kong, where the median house price was more than 14 times the median household income.

Affordability can mean different things, each having their benefits and drawbacks.

One thing it can mean is access to good jobs in economically dynamic cities, like London or San Francisco. When people talk about this version of affordability, they are talking about the economic benefits of access to labour markets, agglomeration, and innovation. When rents and prices are high, talent can’t freely flow to opportunity, and everyone loses out. By some estimates, regulatory restrictions on high-income cities have resulted in a 36 per cent loss in aggregate growth in the US between 1964 and 2009 (though a recent follow-up has suggested the authors underestimated this figure).

When people talk about this sense of affordability, they are thinking of places like Madrid, London, San Francisco, and New York becoming more like Tokyo, in the sense that people can more easily move there to access opportunity.

The second is about reducing rents and prices overall back to some previously acceptable level. When people talk about this version of affordability, they are usually talking about low and middle-income households having access to housing.

Those who are sceptical that “supply” will make housing affordable are usually referring to the second sense of “affordable” and not the first. The intuition they are capturing is that house prices are sticky: they tend not to systematically reverse (unless there is a major economic downturn). When these people talk about affordability, they are talking about places like Vienna.

Commentators sometimes discuss this fact as if there were a conspiracy to keep prices up. But there are structural forces that point in this direction. First, housing is where most people keep their money. A systematic reversal of house prices would be very unpopular, as Donald Trump and Mary Lou McDonald recently noticed. Second, incomes are rising (though, of course, real incomes are being outpaced by house prices). Third, household sizes are changing. And fourth, housing quality gets better over time (driven by preferences, incomes, and yes, regulations), so our new housing costs more in real terms than the new housing of previous generations.

If your answer to this trend is to say “all the more reason to remove the private sector from the process”, then I will point you back to the Demographia report in the above graph: in capitalist Minneapolis, housing is more affordable in some major cities than in Singapore, where the housing system is largely state-controlled. There is more than one way to achieve affordability.

For example, to get the second sense of affordability, many housing systems try versions of price controls. In Ireland, that may be Rental Pressure Zones, to control market rents. It may be “affordable housing”, which is discounted from market prices and available to purchase. Or social housing, which operates through the differential rent system. Or cost rental, where rents are capped at 25 per cent below market levels. Naturally, controlling prices comes with lots of distortions, such as removing the incentive to build, or long queues.

The best housing systems don’t unnaturally block talent from flowing to opportunity. But they don’t forget about normal families and find ways of providing housing at affordable levels even in high-demand areas (though, there are many ways to do this). In short, the best housing systems understand both of these senses of affordability.

ABUNDANCE

Housing in a functioning system should not just be affordable. It should be abundant. These are different things.

Where affordability is about prices, abundance is about quantities. A successful housing system is simply one with lots of houses. There should be more houses than there are households. Between three and five per cent of the total housing stock should be empty.

When there are lots of houses and lots of empty houses, people are free to move to wherever they want to be. When they get a new job, break up with their boyfriend, have twins, or want to follow the bright lights, they can find a new place to live without undue hassle. When a major company has to set up a HQ in a new city, it knows its staff will be able to find their feet.

Abundance and affordability are subtly different. It’s true that places with unaffordable housing tend to have low vacancy rates and a general shortage of housing; and vice-versa. So they do tend to go together. But sometimes they do not.

Abundance and affordability decouple when governments artificially fix affordability using rent controls and related policies. These policies are crudely effective at improving housing affordability. But they do so at the cost of abundance. In places with rent controls, there are usually chronic housing shortages. Landlords are incentivised not to maintain the existing housing stock and developers are incentivised not to add to it. The upshot is that rent-controlled tenants don’t move out of their homes for fear of losing their privileged status, and those without a home can’t get one because there’s no stock on the market.

Abundance also gives people options for the type of home they can live in. A good housing system allows people to move through the housing system throughout their life. But as scarcity is the norm, people tend to be stuck. For example, 68 per cent of 25 to 29 year olds in Ireland live with their parents. In a healthy housing system, one can move into different types of home throughout one’s life.

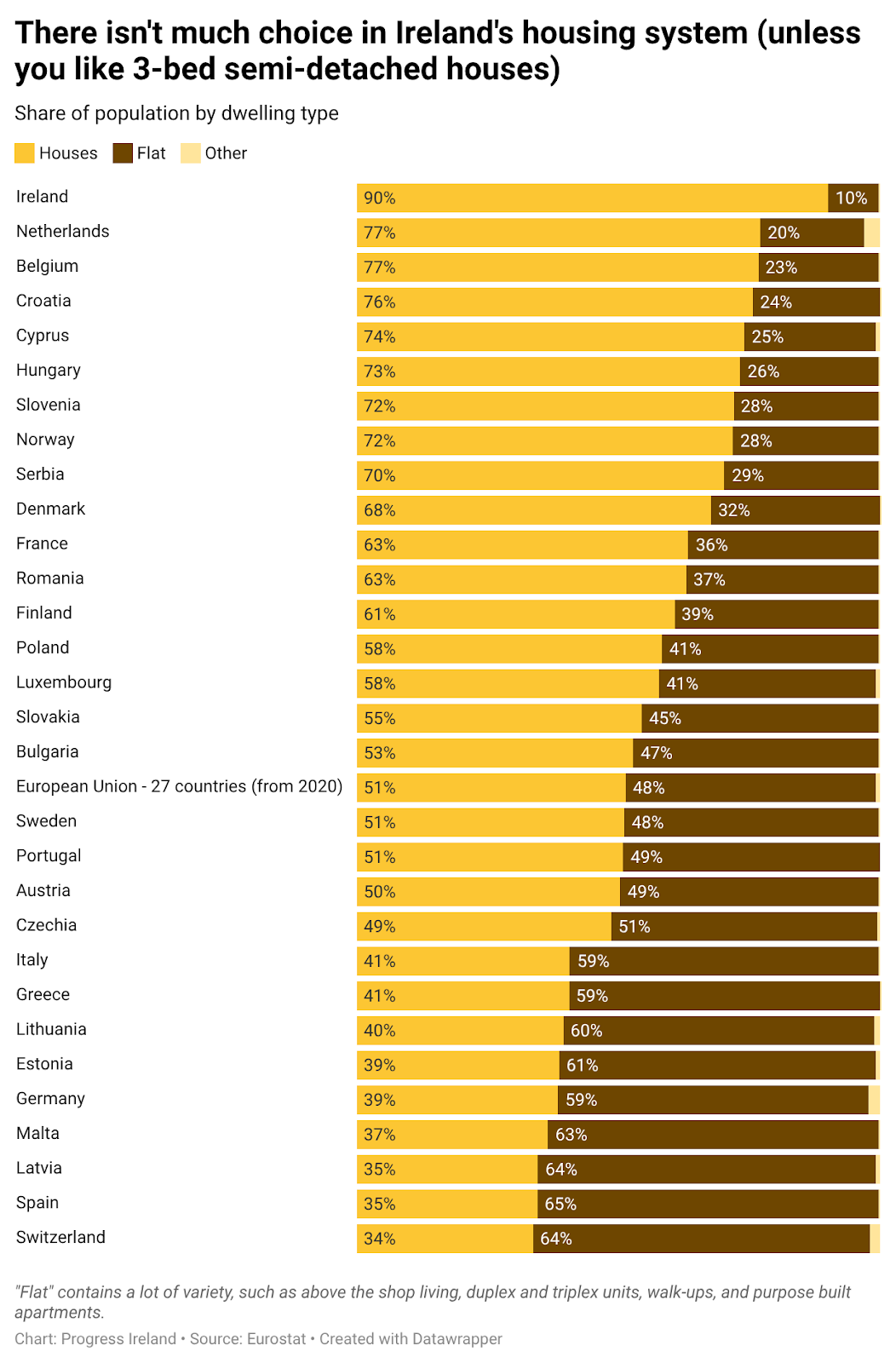

In Ireland, there is little variety in types of home. In fact, Ireland stands out in Europe for offering, predominantly, a single form of housing, a “house”.

In Paris, where incomes are comparable to Dublin, you someone earning below the median income can find a small flat in the central arrondissements. In California, that same household can find granny flats (or seomraí). In Vienna, they could find a cost rental home near the metro. In Amsterdam, there are many homes “above the shop”. In Houston, you can buy a big house with a big garden for relatively affordable prices. A healthy housing system has high quantities of housing, it also offers a wide variety of types of housing.

Quality

A healthy housing system must, first and foremost, be affordable. It must also have lots of houses in it, so people and employers can move around and make plans without worrying about housing.

Is that the end of it? Surely a system in which houses are affordable and abundant is, by definition, working well?

We’re not there yet. The last element of a good housing system is that homes must be good. They have to be worth paying for. They must be dry, warm, and located near to jobs and amenities.

We live in a market economy where housing tends to get built – more or less – where it’s most needed. But not all systems are like this.

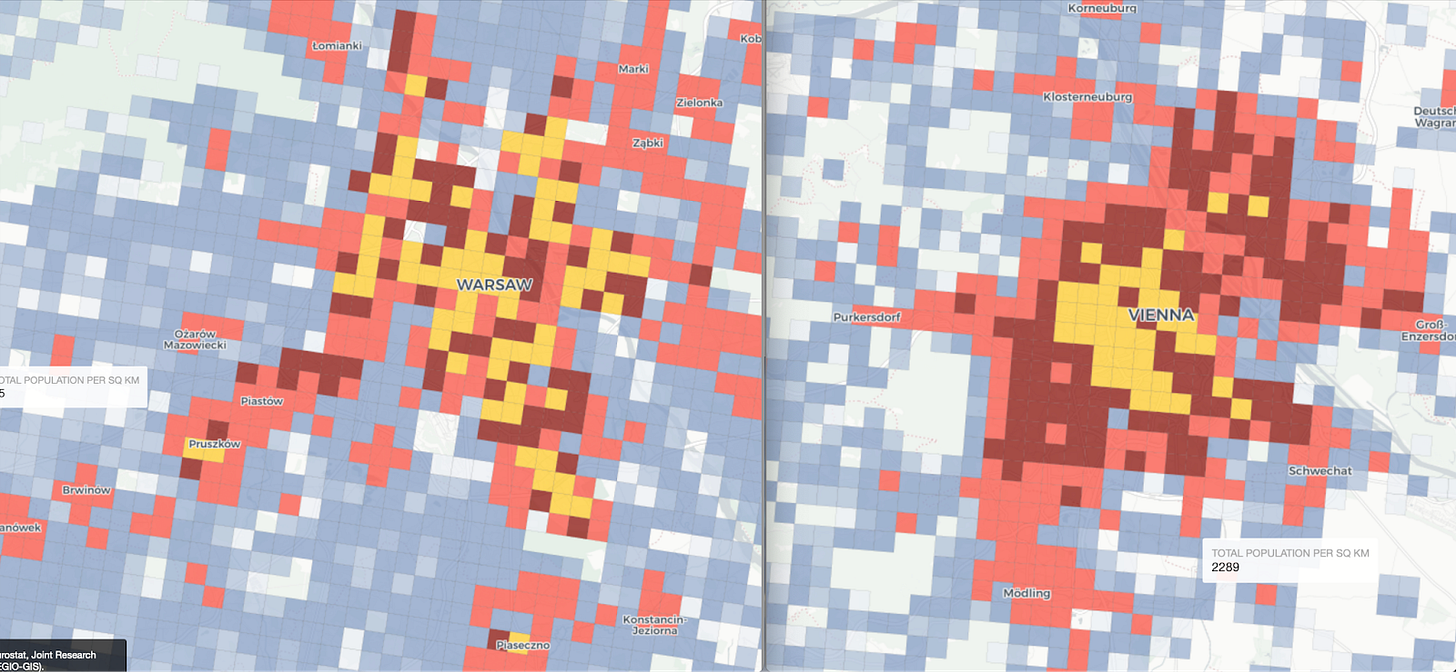

As we’ve seen, rent controls are what you get when governments maximise affordability by any means necessary. At other times, governments maximise abundance by any means necessary. When governments are fixated on building as many homes as possible, they sometimes situate them wherever it’s easiest to build, rather than where they’re most needed. Former Soviet or communist cities, for example, have a strange urban form in which dense apartment blocks are found at the edge of the city, far away from jobs and amenities. The following charts show the density of Warsaw and Vienna. Vianna follows the normal pattern in which the centre of the city (the place with the most jobs and amenities) is the most densely populated. Warsaw resembles a QR code, with random pockets of density across the entire urban area.

Another way the supply of homes is diverted from the areas of highest demand is national plans. The National Planning Framework, for example, aims to divert growth away from Dublin. Governments in India and the UK have attempted to control the growth of cities and divert it in predictable ways. The result of detethering supply and demand in this way is usually that the areas with the highest demand get more constrained and expensive.

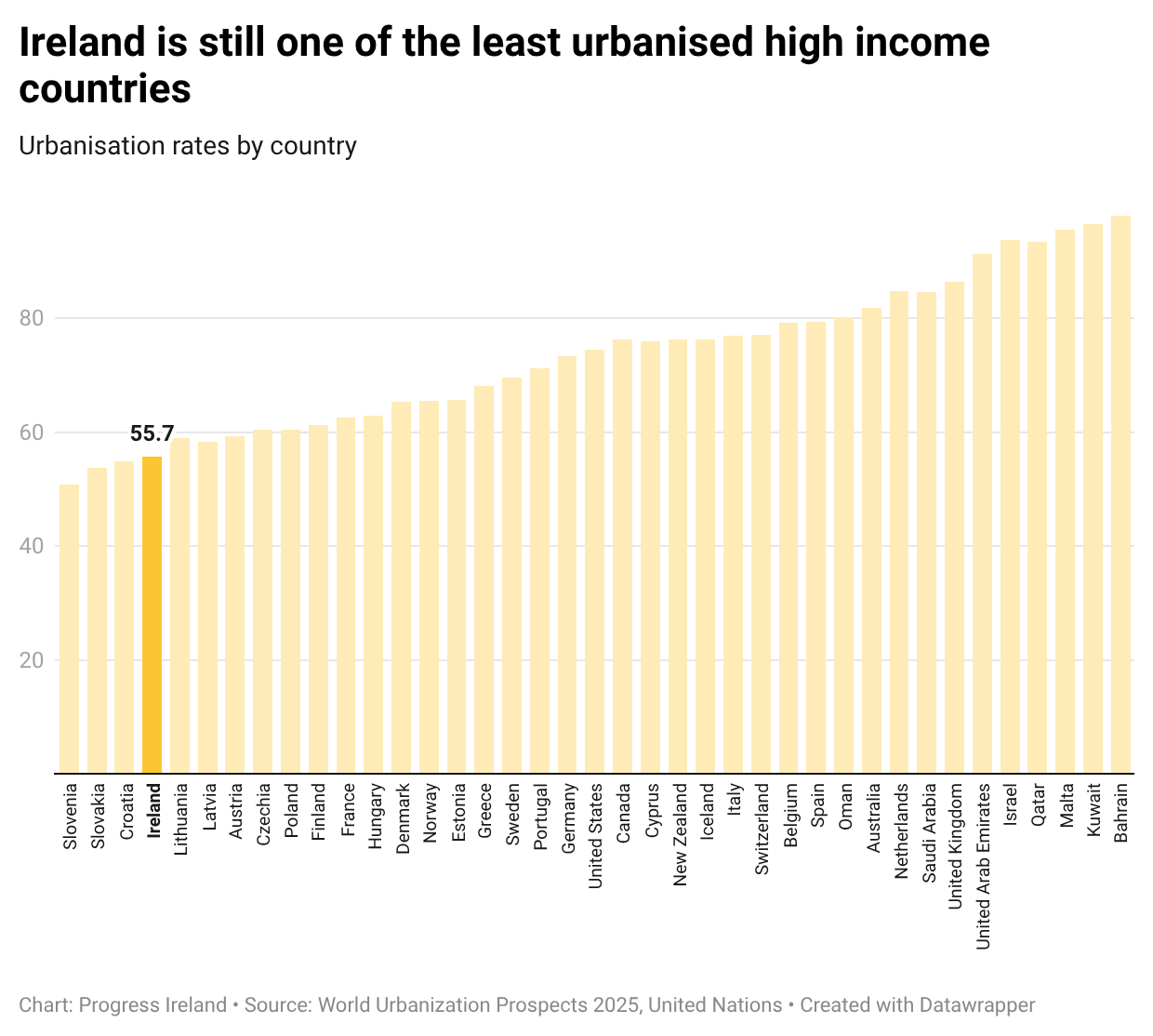

It’s important that housing is located in areas of highest demand. One reason for that is productivity: when people move to more productive areas, they become more productive. According to one French paper, a 10 per cent increase in the number of jobs accessible per worker corresponds to a 2.4 per cent increase in workers’ productivity. This is one reason why it is important that Ireland becomes more urbanised. At the moment, Ireland is one of the least urbanised high-income countries in the world (in 2016, Ireland was at the bottom of the list, but now Ireland is fourth from the bottom due to some newcomers into the category of ‘high income’).

But part of what makes a good location good is how well-connected it is. The best locations are well connected to lots of people, to services like healthcare and schools, to jobs, and to parks and water. This is important for growth because increased access to jobs increases the size of the labour market. For example, a 10 per cent increase in commuting speed increases the size of the labour market by 15-18 per cent.

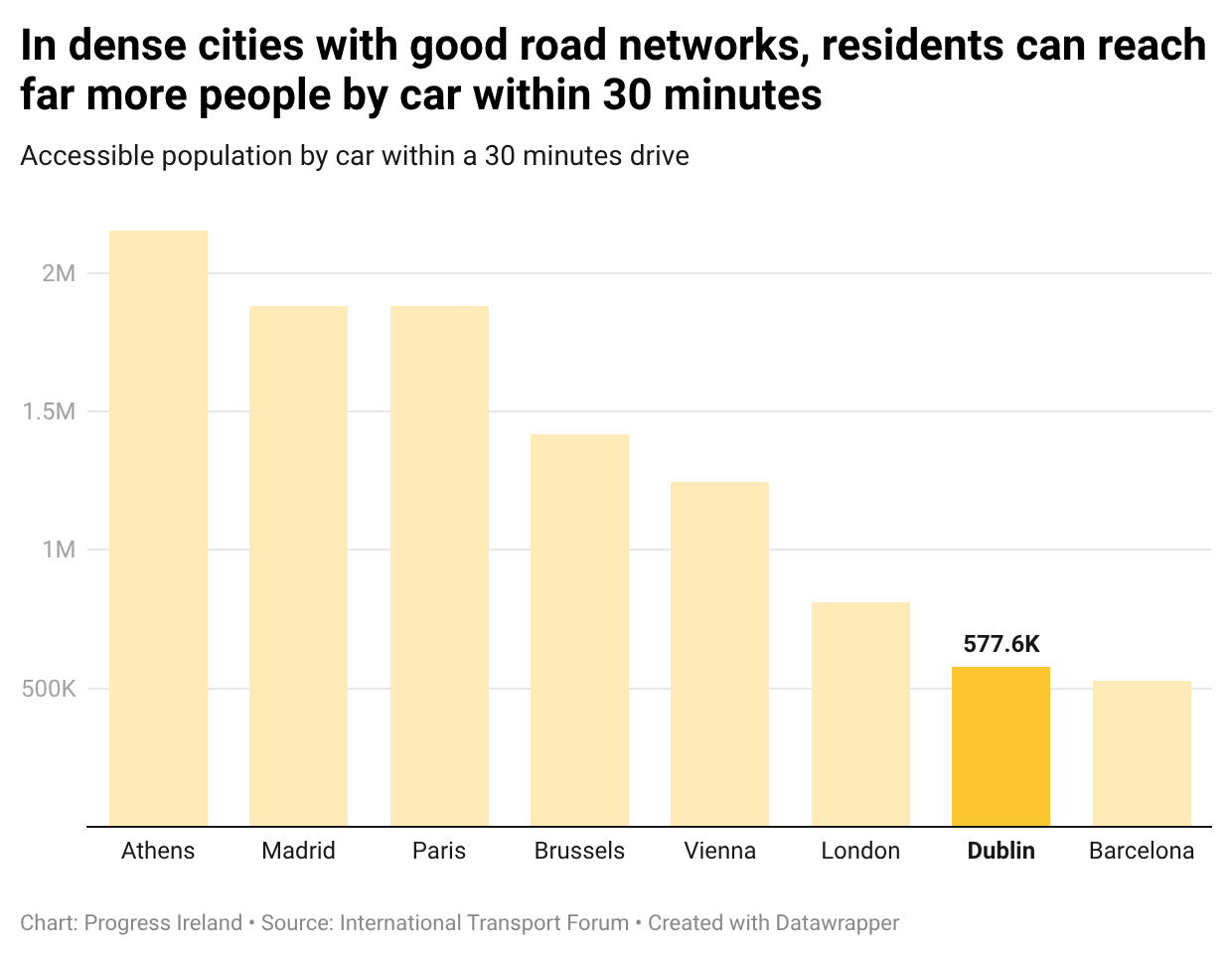

Which cities are the most accessible? More precisely, in which cities do residents have access to the most destinations and other people? A report by the international transport forum has tried to estimate this.

It does this by building a measure of accessibility across 121 European urban areas (the report calls them functional urban areas which are essentially cities plus their commuting zones). They look at getting around by car, on foot, on a bike, and by public transport. They split cities into cells and ask how long would it take, by each mode of transport, to get between cells. They take into account traffic, hills (for cycling), the availability of footpaths for walking, waiting for public transport, and even take into account looking for parking.

A city’s “absolute accessibility” is a combination of two things. First, proximity. In a denser city, residents are closer to lots of things, their jobs, restaurants, hospitals, and so on. Another way to put this is how concentrated is land use in the city? Second is transport performance. How good are the roads? Is there a high capacity rail service, like a metro? Are buses given priority? Is there well-connected cycle infrastructure? In short: how much of what’s nearby can you actually reach within a set time?

The top performers by car are Paris, Madrid, and Athens. For each, over 1.5 million people are reachable in <30 mins by car.

On public transport, Paris, Oslo, London, and Vienna do best. They each have over 600,000 people reachable by public transport in less than 30 minutes. London was the only case where public transport outperforms cars.

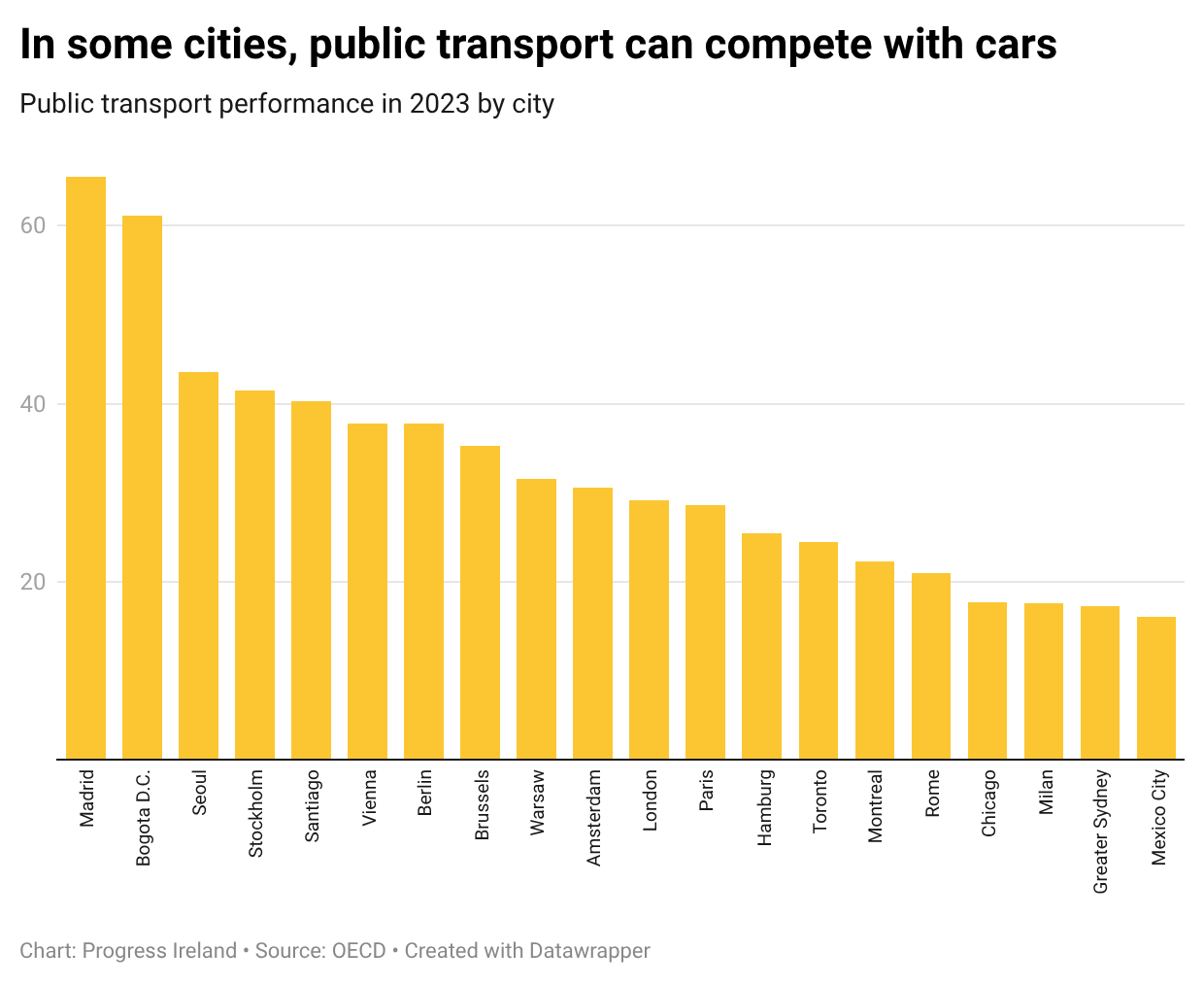

The underlying dataset from the report measures public transport performance relative to driving. For each functional urban area, the OECD estimates two things: (1) how many people an average resident can reach within 30 minutes by public transport, and (2) how many people they could reach within 30 minutes by car in traffic-free conditions. Public transport performance is the ratio of (1) to (2), expressed as a percentage. For example, a score of 30 means that, within 30 minutes, public transport reaches roughly 30 per cent of the people that could be reached by free-flow driving. You can see that in some cities like Madrid, public transport works extremely well.

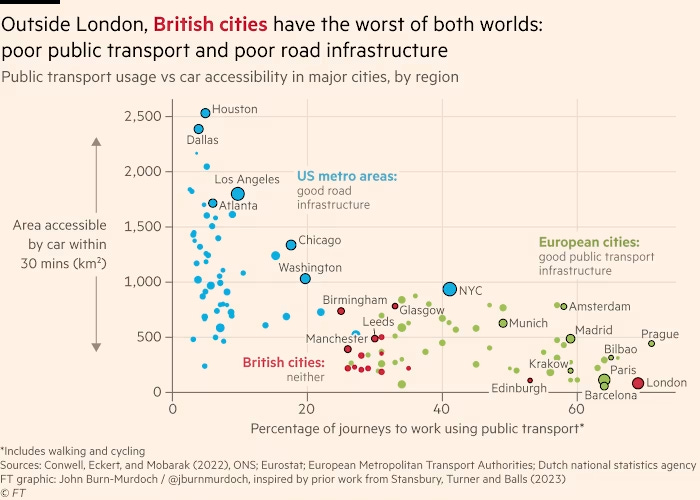

Whether it’s by car, such as in cities like Houston, or by metro like London, or a combination of both like in Madrid, the best housing systems tie housing to transport connections.

It is hard to beat this graph from John Murdoch Burns of the Financial Times which makes this point well. The top left shows the car performance of US cities. It comes with costs but lots of roads are one way to connect huge numbers of people. The best housing systems connect people to each other and things like jobs and services, whether by road or rail.

Abundance solves a lot of problems at once

Healthy housing systems have other virtues, of course. They provide quality housing. New homes are integrated into new urban communities, with access to parks and other amenities. They facilitate great architecture. But they share one thing: abundance.

Abundant homes helps with affordability, it gives people options of where and how they can live, it gives people economic opportunity, and in good systems, it connects lots of people through a good transport system. Solving the housing crisis may mean solving lots of different problems. But solving all of them involves more abundant housing.