In Sophocles’ Antigone, Tiresias, a blind prophet, declares that “[a]ll men make mistakes, but a good man yields when he knows his course is wrong, and repairs the evil. The only crime is pride.”

The same could be said of governments: all make mistakes. But the good ones undo them. Tiresias himself was an experienced government advisor, so we should take his advice seriously.

This government has made some progress on undoing past mistakes. In recent years, too little land was made available to build on. The National Planning Framework (NPF) restricted the amount of zoned land. Recent section 28 guidance, however, instructs councils to zone in excess of the NPF’s targets. Similarly, costly regulations have been partly to blame for high apartment construction costs. These too have been partly wound back. Finally, rental pressure zones (RPZs), some of the strictest rental regulations in the world, have been partly reformed. But, as with all things, there is more to do.

All of these policies began with a nice idea. High apartment standards are not intended to price out ordinary people. They are intended to improve the living standards of apartment dwellers. Similarly, rent regulations exist not to remove the incentive to build more homes, but to protect vulnerable renters. But side-effects exist. Regulations should be judged by their effects, not by their intentions.

With that in mind, consider the following recommendation from the Climate Change Advisory Council (CCAC):

The Government should urgently develop a specific regulation requiring planning authorities to ensure no net loss of biodiversity and that nature-based solutions are incorporated into all future developments.

The intention – to protect biodiversity – is laudable. Recent reports have harshly criticised the state of biodiversity in Ireland. There is a clear need to do something. But we should beware of a common pattern in policy making.

First, a problem is identified. For example, take the energy efficiency of housing. Our existing stock isn’t very energy efficient: looking at the rental stock alone, the ESRI has found that 80 per cent of rental dwellings in Ireland have a BER rating below B. The majority of these are D (24 per cent) or C (38 per cent) rated.

Next, a solution is mandated. However, the effects might not be what are expected. In this instance, the government required all new residential buildings to be, at minimum, A2 rated. This means that what gets built has a higher BER rating. But it also means that new homes are scarcer and more expensive. The cost was levied on new homeowners and renters.

According to the government’s own regulatory impact assessment, this move meant an increase in construction costs in the region of 0.7 per cent to 4 per cent, depending on the type of development. On its own, it may not seem like much. But the minimum spec home, especially if that home is an apartment, was extremely costly before these changes (hard construction costs alone at the time were about €250,000 per two bed apartment). After the changes, these homes became even more expensive to build.

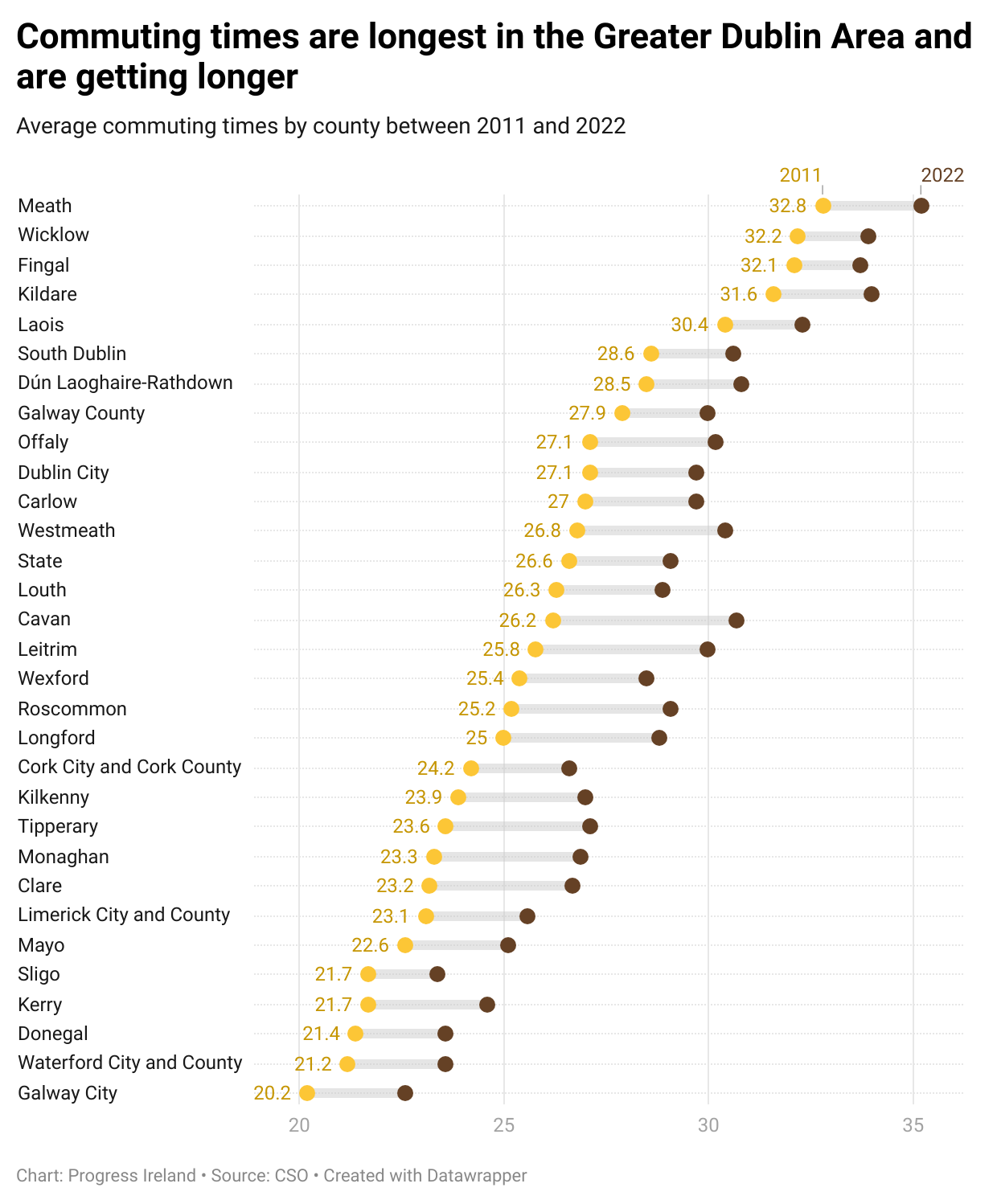

There is an additional way for this policy to backfire. Yes, what gets built is of higher quality. But, due to the high costs, more and more people are forced to live far away from their work. And more commuting means more emissions.

Sometimes when you aim for higher quality homes, you get fewer, more expensive, and more dispersed homes. The lesson here is that the second order effects of policy really matter.

Back to biodiversity

What does this mean for the biodiversity proposal by the CCAC?

First, the one thing it does not mean is that the government should do nothing. If we are to combat the decline in biodiversity, the government needs to act.

Second, it means we take the second order effects seriously, and seek to minimise the harm done to those that need a home, among other national goals. How might this be done?

Project by project

Some environmental assessments must be applied on a project by project basis. For instance, EIAs and AAs must be carried out, at least sometimes, on a project by project basis. That means that with each new planning application comes a new set of environmental assessments. Without reforming pieces of European environmental law, there is no way around this for Irish policymakers.

A new regulation, such as that proposed by CCAC, would not be under the same European constraint. Should such a regulation be applied on a project by project basis?

There are two important reasons to resist any new project by project regulation. The first relates to delays and the second to efficiency.

First, delays. Large scale development is already overburdened with paperwork (a given application will often run into the 1000s of pages). It takes a lot of time to compile and write-up the evidence in these applications. Deciding on the precise mitigation measures, if any, also takes a lot of time. Piling on additional measures at this stage would make a difficult and costly process more difficult and more costly.

Second, efficiency. There is some evidence that site specific remedies are often not always the optimal place to mitigate biodiversity damage. Famously, Britain’s HS2 ‘bat tunnel’ spent £330,000 per bat. Plainly, in bat-maximising terms, that money could have been spent more efficiently.

But CCAC’s proposed measure, if enacted, doesn’t have to be project by project. The UK’s Planning and Infrastructure bill proposes a strategic “nature restoration fund.” Under the proposed regime, developers would not have to carry out their own costly surveys. Rather, they would rely on strategic environmental assessments, carried out over a larger area. Notably this cost would be borne by the public, rather than solely on those who buy or rent newly built homes.

If the project involves some environmental damage, the developer has two options. They can take site specific action or they can pay into the nature restoration fund, which funds mitigation at a strategic level.

The proposed British system is imperfect. But it would mark an improvement from the UK’s current system. The current system is the worst of both worlds: it is costly and hasn’t helped biodiversity. That brings us another potential problem for CCAC’s proposal: its cost will fall on urban development.

In Britain, the cost of a requirement known as ‘Biodiversity Net Gain’ or BNG has fallen mostly on small urban developers. BNG requires all new (but for a small set of exemptions) developments to contribute an increase in biodiversity of 10 per cent.

However, before the requirement for BNG, most large homebuilders were voluntarily committing to net gains in biodiversity. Rather than falling on big homebuilders, the marginal cost of the regulation seems to have fallen on small infill sites.

The reason for this is twofold. First, brownfield urban sites are (perhaps surprisingly) diverse habitats compared with agricultural land. And second, it is more expensive to build in urban areas (mostly because it is apartments, and not houses, that are being built).

This suggests another way in which this policy, if not enacted carefully, could backfire: it could further squeeze urban development. Since it is national policy to grow Ireland’s urban areas, so-called ‘compact growth’, it is important that any additional biodiversity requirements do not limit Ireland’s ability to deliver urban housing.

All regulations, existing and new, should be judged by their outcomes, not by their intent. Tiresias would praise this government for undoing harmful regulations. However, he would caution it to not introduce new ones in their stead.