Last week, residents of Dartmouth Square in Ranelagh popped up to offer Ireland a lesson about concentrated costs and diffuse benefits.

Some Dartmouth Square residents took a judicial review against Metrolink. Their JR could delay the project by anything from six months to two years.

The benefits to Dublin of Metrolink are clear: shorter commutes, higher incomes, more housing. The 2021 business case estimated Metrolink would generate €700,000 in benefits for the people of Dublin, per day. And those benefits would be shared widely.

The costs of Metrolink are not shared as widely. They’re felt more intensely by people who, for example, will live on leafy Victorian squares near stations during the construction phase.

A benevolent God-King would weigh up the costs and benefits to Dublin as a whole, and would then adjudicate that the project should go ahead. Dartmouth Square residents would be eggs in the Metrolink omelette.

But there are no God-Kings. We’re ruled by laws, drafted by lawmakers, who are elected by voters, and who want to keep their jobs. This system is vulnerable to coordinated campaigns by small groups of highly motivated people. The Dartmouth Square residents whose windows will be rattled during Metrolink’s construction will ring their councillor, or TD, or pay lawyers to scrutinise planning applications.

The beneficiaries of Metrolink – would-be buyers of new homes in Swords, or commuters who’ll each save time on their daily commute – won’t make the same effort. It’s too hard to organise a campaign among 650,000 people who each benefit slightly or hypothetically.

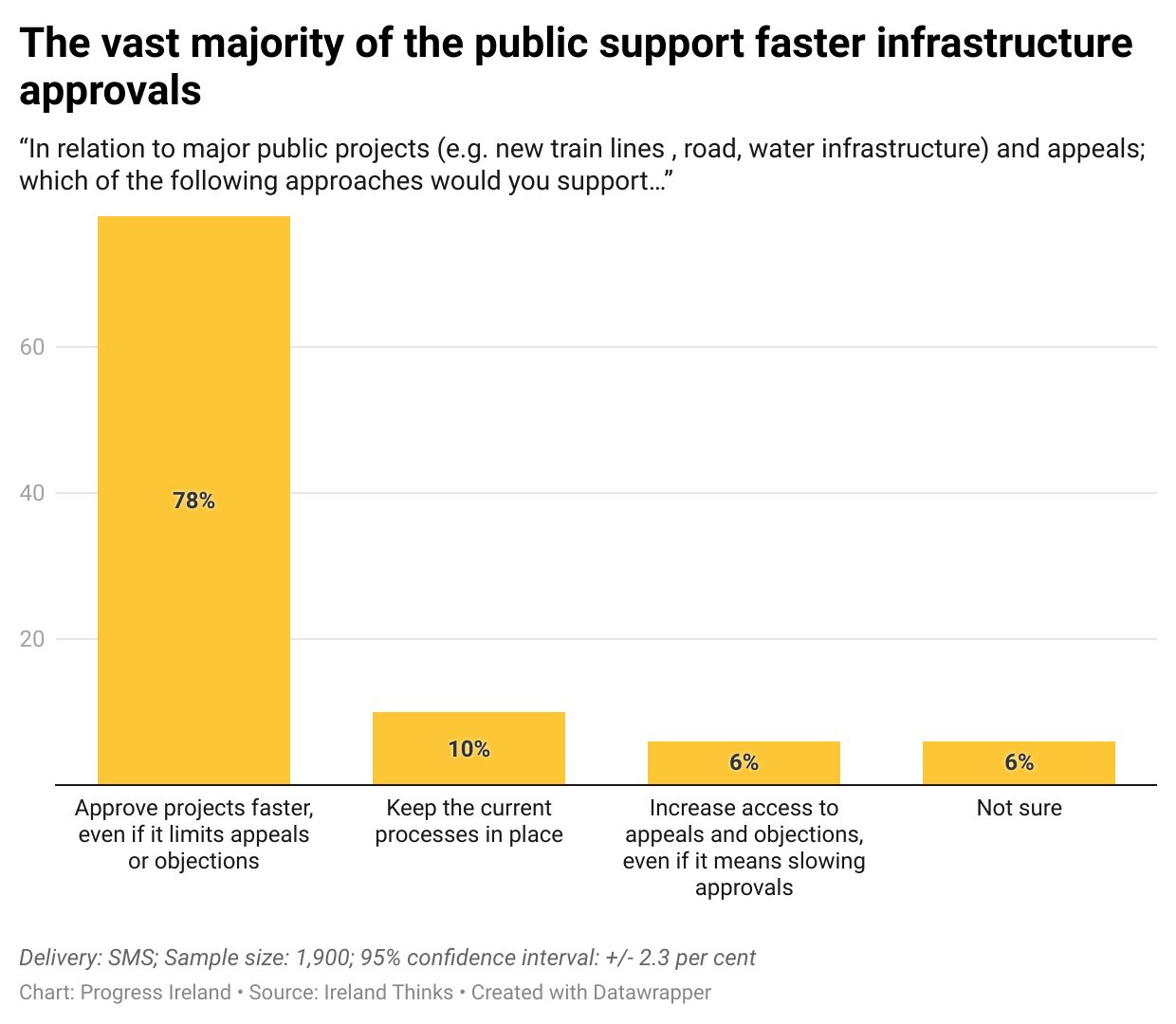

For what it’s worth, the public is squarely in favour of more infrastructure. In a poll commissioned by Progress Ireland, 78 per cent of the public said they want faster major project infrastructure approvals, even if that means limiting appeals and objections. A Business Post poll found 56 per cent of the public were in favour of emergency powers to build infrastructure.

It’s helpful that the public is onside. But as we’ve seen, in our system, the key players are not the voters. The key players are the small, motivated, organised groups that oppose projects. The intensity of preferences matters a lot.

Last week the government launched its Accelerating Infrastructure Report and Action Plan. It’s a good plan. It diagnoses the problem correctly and sets out 30 actions, with dates attached (you can track whether the government has enacted the report’s 30 actions on schedule on Progress Ireland’s tracker here). If the system aligns around the report and follows through it – a big if – it could make a big difference to Ireland’s ability to build.

The plan highlighted the problem of distributed benefits and concentrated costs. It said: “The benefits of infrastructure tend to be widely dispersed, while the perceived costs such as disruption, visual impact, and loss of amenity are concentrated at a local level. This imbalance can fuel opposition from affected communities.”

There are two ways to tackle that problem. The first is what I have called the Green Jersey approach. This approach says, when there are many more winners than losers, the losers should don the green jersey. And if they won’t pull on the jersey, they should be compelled to do so.

There’s some merit in the Green Jersey approach. European countries like France and Spain – better infrastructure builders than Ireland – tend to brook much less nonsense when it comes to public consultation. After the consultation a decision is made, and that’s often the end of it. But there’s also a limit to what the state can – and should – get done by bossing around its citizens. Citizens have rights, and what’s more, in the long run they write the laws.

The best option, where possible, is to co-opt objectors. I’ll call this the win-win approach. New infrastructure creates a lot of value. When enough value is created, there is an opportunity to compensate the would-be losers. For example, a rezoning decision can increase the value of a plot by 8,400 per cent.

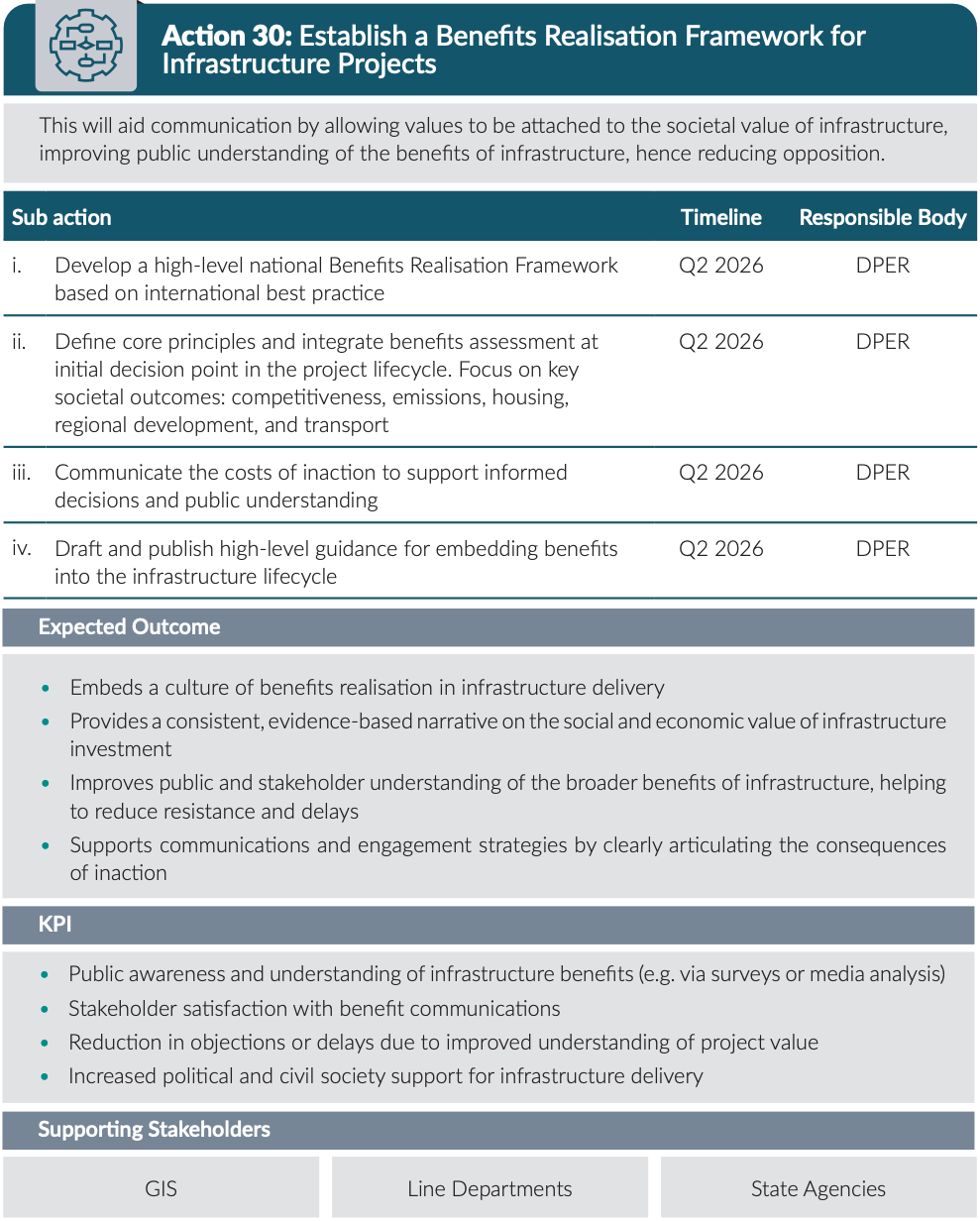

This brings us to Action 30 in the Accelerating Infrastructure Report: the creation of a Benefits Realisation Framework.

The wording is somewhat unclear. It will outline the overall benefits precisely, allowing decision makers and stakeholders to see what is “in it” for them. But subaction four is to “embed benefits into the infrastructure lifecycle” with the explicit aim of fostering support for major projects. This gets at the heart of the problem of diffuse benefits and concentrated costs.

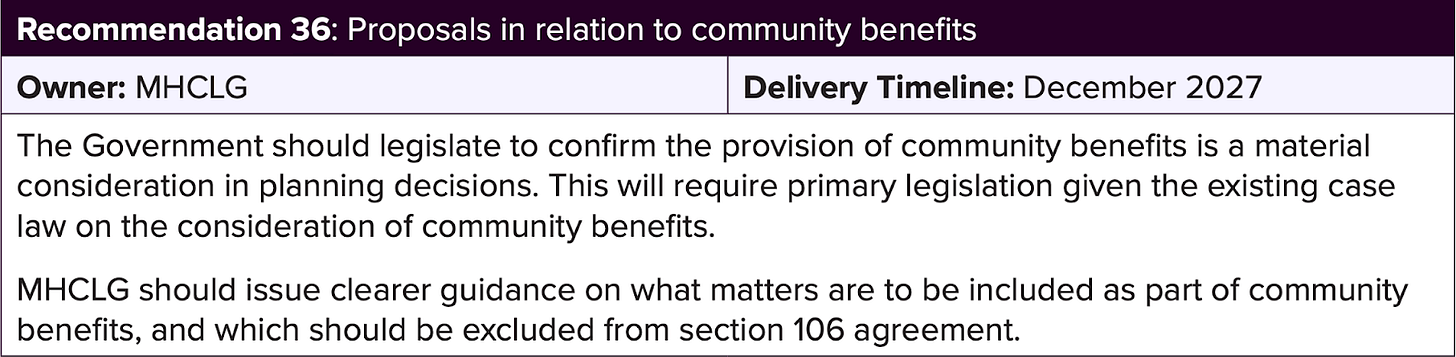

Reading action 30 reminded me of another recent governmental report on infrastructure, John Fingleton’s Nuclear Regulatory Review Taskforce in the UK. Here is recommendation 36:

Recommendation 36 directly targets the incentives of locals. It says communities that host infrastructure should be allowed to specifically benefit from it. Otherwise, you end up with a system that incentivises obstruction. When you combine the incentive to block a project with the means to do so, you shouldn’t be surprised when many major infrastructure projects end up in the courts.

Compensating communities for hosting infrastructure is not a new idea. France built a world-leading nuclear power industry, in part, by enabling lower taxes in the communities that hosted the reactors. Avoine, the commune that hosted the first EDF reactors, for example, saw annual revenue jump 100x in ten years.

There are more subtle but nevertheless powerful versions of this idea. ‘Fiscal zoning’ refers to the idea that some areas attract development and industry in order to raise revenue and decrease the overall tax burdens on residents. The basic idea is that there is a tight connection between the fiscal benefits of building and local costs of building.

To be sure, infrastructure developers in Ireland offer community benefits. Many types of development are associated with “community benefit funds”. For example, all RESS projects must pay €2/MWh into a community benefit fund. An incinerator in Dublin has paid over €10 million into a community gain fund. Wind Energy Ireland also reports the success of their fund here.

What about the objection that community benefits will only incentivise opposition? This is a fair point. It's important that benefits are ruled-based and automatic, rather than ad-hoc. Ad-hoc community benefits are the worst of both worlds, in that they encourage opposition rather than nullify it.

This is all of a piece with the Progress Ireland approach to planning. We think it’s worth creating mechanisms communities can opt-into. The mechanisms are designed to incentivise stakeholders to act in the common good, with carrots and sticks. We’ve built one for suburban intensification and one for big brownfield/greenfield sites.

But the effectiveness of the French system and the promise of the Accelerating Infrastructure Report come from putting community benefits at the heart of the system. If everyone knows that more development in their area will materially improve their lives, it could be less a case of diffuse costs and concentrated benefits, but of local areas vying for a chance of enjoying the concentrated benefits that will come with infrastructure delivery.